Written By Idowu Ephraim Faleye – 08132100608

In a recent address, the Sultan of Sokoto, Muhammad Sa’ad Abubakar III, described social media as a terrorist organization, citing its role in spreading false information and inciting unrest. This bold statement sheds light on a growing tension in Nigeria’s power dynamics—why the Sultan fears social media. In truth, it’s because social media has become the people’s weapon against Nigeria’s entrenched power establishment. For millions of Nigerians, especially those from historically marginalized regions and groups, social media has become a voice, a weapon, and a mirror reflecting the rot in the system that traditional media often failed to expose

Before the internet, communication in Nigeria was a difficult, often exclusive process. When someone needed to pass a message, one had to travel physically or send a letter through the postal service, which took days or even weeks. Expressing public opinions required access to print media, radio, or television, all of which were not only expensive but also heavily censored. Only the privileged, those with the means and connections, could afford to be heard. Voices that challenged the status quo were filtered or silenced altogether. However, the coming of the internet, and more specifically social media, has completely overturned that order. Today, with an Android phone and data subscription, an ordinary citizen in a remote village can speak directly to the nation, if not the world, without needing permission or financial muscle

The rise of platforms like Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp, TikTok, and YouTube has revolutionized how Nigerians engage with information. With over 103 million Nigerians connected online as of 2024 and a significant portion actively participating on social media, the monopoly of traditional media has been shattered. Issues that once simmered quietly behind closed doors now erupt online in seconds, exposing corruption, injustice, violence, and manipulation in real time. The spontaneity and decentralization of citizen journalism have replaced the gatekeeping role of the elite.

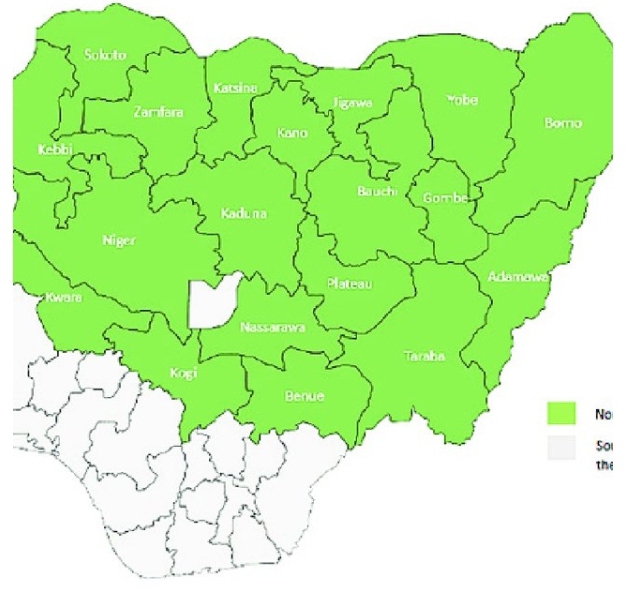

It is in this light that the Sultan’s statement should be understood. Social media is a “terrorist,” not because it wields bombs and bullets, but because it strikes fear into the hearts of those who have long held sway over public narratives unchallenged. The Sultanate, being a symbolic head of the Fulani oligarchy that has enjoyed dominance in Nigeria’s religious, political, and economic structures, now finds itself constantly scrutinized. Social media has unmasked long-suspected agendas and disrupted the monopoly of history writing, propaganda, and public influence once held tightly by northern political elites.

Read Also: Where Do the World’s Richest People Come From? A Data-Driven Look at Global Billionaires

The history of the Fulani oligarchy, rooted in the Jihad of Uthman dan Fodio and the subsequent establishment of the Sokoto Caliphate, has long been debated in hushed tones across the country. While some see it as a religious and cultural heritage, others interpret it as the beginning of a deliberate agenda of conquest, domination, and marginalization. Stories like the age-old claim that the Fulani planned to “dip the Qur’an into the ocean” once remained on the fringes, dismissed as conspiracy. But today, these conversations have entered mainstream discourse, dissected daily by millions on social media. Videos, articles, and personal testimonies flood timelines, challenging narratives that were once beyond question.

One of the biggest blows social media has dealt the oligarchy is the increasing awareness among the Hausa population, who, for decades, have been politically and culturally dominated by the Fulani elite. The access to diverse information has stirred introspection among young Hausas, many of whom are now questioning religious dogma, political loyalties, and the elite’s use of Islam as a tool for control. It has created a ripple effect of awakening that is reshaping northern Nigeria’s political and religious landscape. This digital enlightenment has also emboldened many other ethnic groups to speak out about systemic injustices—be it resource allocation, lopsided political appointments, or manipulation of national institutions.

For instance, social media played a crucial role during the 2023 elections in Nigeria, where it was used not only to campaign but also to expose vote-buying, ballot snatching, and manipulation of results. Videos of electoral malpractices that would have been denied or downplayed in the past went viral within minutes, leading to national outrage and legal action. During the End SARS movement, the Nigerian youth used social media to organize one of the largest protests in recent times, calling for an end to police brutality. They raised funds, coordinated logistics, and gained international attention—all without relying on traditional media.

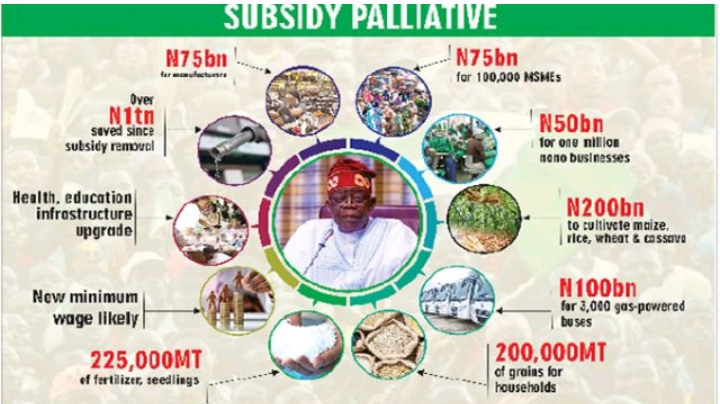

Therefore, it is understandable that the same social media that gives the people a voice and agency is perceived by the Sultan and the elite as a terrorist. It is not just tormenting them—it is unseating them from the thrones of unchecked power. It is dragging their secrets into the sunlight and holding them accountable in once unimaginable ways. The things that used to be swept under the carpet—rigged census figures, religious manipulation, budget padding, illegal resource transfer, structural imbalance, and the alleged funding of Sahel countries with Nigeria’s money—are now daily topics of open conversation. The control over public perception is slipping away, and those who thrived in opacity are gasping for relevance.

Read Also: Forgotten and Forsaken Inside the Nigerian Prison System

Today, Nigerians are more informed than ever. They know who controls the NNPC, who dominates the national security structure, who dominates the foreign exchange market, and how national appointments are made to favour certain regions in the past. They are connecting the dots between poverty in the south and resource allocation in the north, between insecurity in the middle belt and political calculations of the Sokoto Caliphate. And all of this has been made possible not by newspapers or NTA news at 9 pm, but by thousands of anonymous digital foot soldiers sharing videos, screenshots, voice notes, and lived experiences.

This is why many Nigerians, especially in the South, are unapologetic in their support for what the Sultan called the “terrorism” of social media. For them, it is a beautiful chaos—one that disrupts the plans of those who plan in secret. It is a loudspeaker for the oppressed, a tool of resistance, and a bridge of solidarity across tribal and religious lines. It is the equalizer in a country where inequality is manufactured from the top. Yes, social media has its flaws—it can be abused, manipulated, and used for misinformation—but it remains one of the best things that has happened to humanity.

Read also: Kidnapping in Nigeria: A National Emergency That Demands Immediate Action

There was a time when it would take months for an injustice to be known, and even then, only if the media chose to report it. Today, within minutes, videos of human rights violations, ethnic violence, or policy failures can go viral and trigger a national response. That is why social media continues to survive every attempt to stifle it. Because the people know what it means to be voiceless, to be invisible, to be lied to and told it is the truth. They have found a weapon, and they will not drop it—not even when it offends royalty.

In the end, the Sultan is not wrong to feel tormented. He is not wrong to feel that the foundations of his inherited influence are shaking. But this is not terrorism; this is transformation. The people are no longer subjects—they are stakeholders. They are not waiting to be spoken for—they are speaking. And even if it unsettles the throne, it must continue.

Because for every child whose future was stolen by a system that thrived on silence, for every village that was wiped out while leaders looked away, for every truth buried under propaganda, this so-called terrorism of social media is justice rising from the ashes. It is the cry of the people becoming a chorus. It is the past finally meeting the present in a fair fight. And in that fight, the people have finally found their sword.

Idowu Faleye is the founder and publisher of EphraimHill DataBlog, a platform committed to Data Journalism and Policy Analysis. With Public administration and Data Analytics background, his articles offer research-driven insights on Politics, governance and Public Service delivery.

![The Trend of Insecurity in Nigeria. [Part 2]](https://ephraimhilldc.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Computer-Monitoring-of-Remote-areas.png)