By Idowu Ephraim Faleye +2348132100608

Early warnings are meaningless when they are seen, acknowledged, and then ignored. In the previous article, the warning signals were laid bare—repeated attacks, familiar locations, predictable timing, and a disturbing consistency in targets across the Southwest. Those were not coincidences; they were data speaking in patterns. But recognition alone does not stop violence. The real cost emerges when analysis fails to move from detection to projection, from awareness to action.

This follow-up goes beyond identifying signals to confront the uncomfortable question many prefer to avoid: what happens next if nothing changes? By projecting risk from the already visible trends, this analysis exposes the future that awaits the Southwest if deliberate intervention is delayed—one where today’s warnings become tomorrow’s tragedies, and silence becomes complicity.

Security threats rarely jump from calm to chaos overnight. They move in phases. Each phase leaves traces that can be seen by anyone willing to look closely. The Southwest is currently in such a phase, one that sits between disruption and consolidation. Understanding this phase correctly is the difference between prevention and regret.

The first phase we must understand is what happens after armed groups lose strongholds. When pressure is applied in one region, groups do not vanish. They fragment. They become smaller, quieter, and more mobile. Their immediate goal shifts from confrontation to survival. This is the stage where relocation happens, where fighters blend into civilian movement, and where forests and remote areas become attractive. Data from multiple regions shows this pattern repeating across different conflicts.

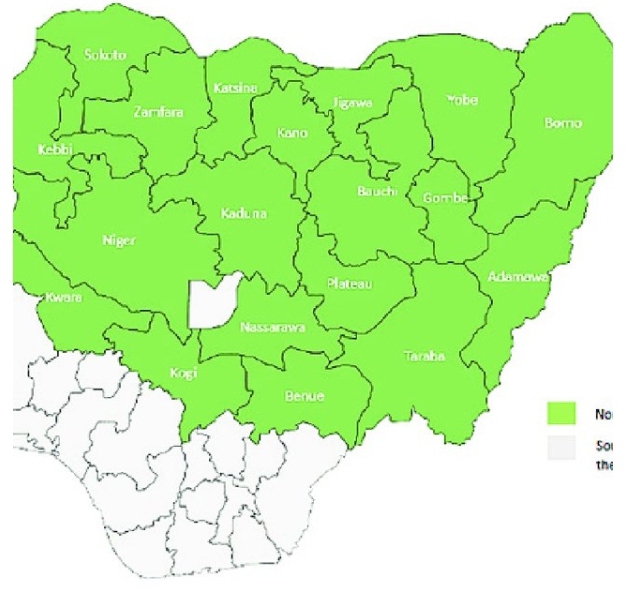

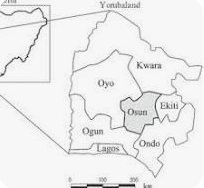

In the current context, pressure on terrorist and bandit networks in the North and across the Sahel has disrupted established systems. Intelligence reports, public statements, and observed movements confirm that some elements have moved southward. This movement is not random. It follows routes, terrain, and opportunity. The Southwest, with its forest belts and inter-state corridors, fits this logic.

At this stage, armed groups focus on three things. First, they look for places to hide. Second, they look for ways to rebuild capacity. Third, they test their environment quietly to understand local response strength. Each of these activities leaves indicators. When these indicators are ignored, groups gain confidence and time.

Read Also: A Wake-Up Call to the Newly Constituted South West Development Commission

One clear indicator is settlement behavior. Forests close to towns provide cover and access at the same time. They allow groups to observe daily life, security routines, and response times. This is not accidental. It is deliberate positioning. Once settlements are established, even informally, they become bases for future action.

Another indicator is target selection. When attacks focus on security facilities rather than markets or mass civilian spaces, it suggests preparation rather than terror messaging. Groups that are not fully armed prioritize weapon acquisition. They attack police posts, patrol units, or poorly defended installations. The goal is not publicity. The goal is supply.

If this phase continues without disruption, the next phase becomes predictable. Consolidation follows survival. Groups begin to stabilize. They establish command structures, even if loose. They recruit locally or link with existing criminal networks. Funding mechanisms expand, often through kidnapping, extortion, or protection rackets. At this point, attacks may actually reduce for a short time, creating a false sense of calm.

Read Also: Saving Yorubaland from Fulani Invasion Before It’s Too Late

This reduction in visible violence is one of the most dangerous moments in any security cycle. Silence is often misinterpreted as success. In reality, it can mean preparation is complete. Data from other regions shows that major attacks are often preceded by a period of relative quiet. This is why analysts must treat sudden calm after early warnings as a signal, not a relief.

Another likely development is the shift in target profile. Once weapon needs are met, attacks move away from security posts toward softer targets. Civilian communities, transport routes, and economic infrastructure become more attractive. These targets create fear, generate funds, and weaken public confidence. At that point, the cost of response rises sharply.

There is also a regional dimension that must be considered. Armed groups do not respect administrative boundaries. Forest routes cut across states. Criminal networks operate where coordination gaps exist. If each state responds in isolation, pressure in one area simply pushes activity into another. This creates a moving problem rather than a solved one.

From a data perspective, this creates a compounding risk. Disconnected responses increase blind spots. Blind spots allow consolidation. Consolidation leads to escalation. This sequence has been observed repeatedly in conflict zones where early coordination failed.

Another important factor is local perception. Communities living near forests often sense danger before authorities do. Their concerns about strange movements, new settlers, or unusual night activity are early indicators. When these concerns are not integrated into intelligence systems, valuable data is lost. Community fear then turns into mistrust, and mistrust reduces cooperation.

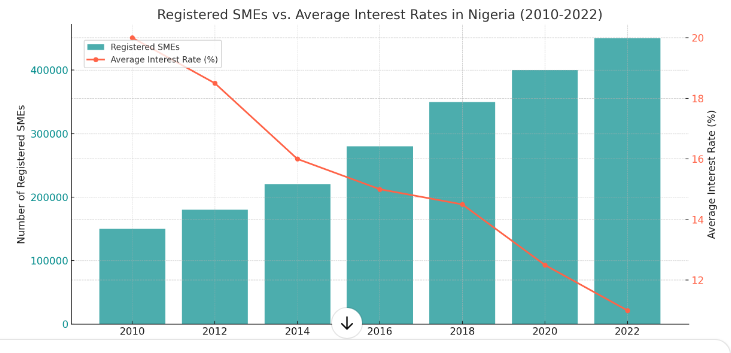

The economic cost of delayed action must also be considered. Preventive measures are cheaper than crisis response. Early surveillance, intelligence coordination, and targeted disruption cost far less than prolonged military operations, humanitarian response, and reconstruction after major attacks. This is not speculation. It is a documented pattern across multiple regions.

Traditional security approaches struggle in this phase because they are designed for visible threats. Patrols respond to incidents. Checkpoints stop vehicles on known roads. Raids follow attacks. None of this address hidden movement in forest terrain. None provide persistent visibility. None shorten the gap between movement and detection.

This is where intelligence-led operations become critical. Intelligence-led does not mean aggressive. It means informed. It means collecting data continuously, not episodically. It means understanding terrain, movement patterns, and behavior over time. It means acting before an attack threshold is crossed.

Surveillance technology plays a central role here. Drones are not solutions on their own. They are tools for data collection. When used properly, they provide persistent visibility over areas that are otherwise blind. They allow security agencies to see patterns of movement, detect temporary camps, and identify changes in terrain use. This data, when combined with ground intelligence, becomes actionable insight.

The value of surveillance is not in dramatic footage. It is in routine observation. It is in noticing when something changes. When a new path appears. When movement increases at odd hours. When camps appear and disappear. These are signals that matter.

However, surveillance without coordination is wasted effort. Data must flow. Intelligence must be shared across states and agencies. A forest in one state may serve as a route into another. If monitoring stops at administrative borders, groups will exploit that gap. Regional coordination is not optional. It is essential.

Another critical element is response timing. Early disruption is less violent and more effective than late confrontation. Removing camps, intercepting movement, and disrupting supply chains at an early stage prevents groups from stabilizing. Once stabilization occurs, every action becomes harder.

There is also a need to regulate space, not just patrol it. Forests are not lawless by nature. They become lawless when ignored. Mapping, zoning, and controlled access reduce anonymity. Anonymity is a key asset for armed groups. Reducing it increases friction and risk for them.

From an analytical standpoint, the Southwest is at a decision point. The data does not yet point to a fully mature threat. It points to an emerging one. Emerging threats can still be shaped. Mature threats must be fought.

This distinction should guide policy choices. Overreaction can be as damaging as inaction. Heavy military presence without intelligence can alienate communities. Ignoring early signals allows consolidation. Balanced, data-led action reduces both risks.

It is also important to manage public communication carefully. Fear spreads faster than facts. Clear, calm messaging builds trust. When people understand that actions are preventive, not reactive, cooperation improves. Community intelligence becomes stronger. Panic reduces.

Another risk scenario worth considering is the blending of criminal and terror networks. This has already happened in parts of the North. When ideological groups and profit-driven criminals intersect, violence becomes harder to predict. Motivations diversify. Funding increases. This intersection often happens during consolidation phases.

If early warnings are ignored, such blending becomes more likely. Forest-based groups connect with kidnapping rings, smugglers, and illegal miners. These connections provide money and logistics. Once that happens, removing them becomes far more complex.

Data also suggests that early success stories often go unnoticed. Prevented attacks do not make headlines. Disrupted movements remain invisible to the public. This creates a challenge for policymakers, who may not receive credit for prevention. But prevention remains the most effective strategy.

For analysts, the responsibility is to keep pointing to signals, even when they are uncomfortable or inconvenient. The role of analysis is not to confirm comfort. It is to reduce surprise.

In the current case, the signals are consistent. Forest proximity. Weapon-focused attacks. Migration indicators. Intelligence alerts. Geographic clustering. None of these alone prove a conclusion. Together, they form a pattern that cannot be dismissed.

The question is no longer whether there is a risk. The question is how that risk will be handled. Will action come early, when options are many and costs are low, or later, when choices are limited and damage is already done.

From a data-driven perspective, the recommendation remains clear. Increase persistent visibility over forest areas. Integrate community reports into intelligence systems. Share data across state boundaries. Act on early indicators rather than waiting for escalation. Invest in prevention infrastructure now, not after crisis.

Security failures are rarely sudden. They are usually the result of ignored warnings. Data gives us the advantage of foresight, but foresight only matters when it informs action.

The Southwest still has time. The signals point to an early stage. The path forward depends on whether decision-makers choose to listen to the data or wait for confirmation through tragedy.

This analysis is not a prediction of inevitable violence. It is an argument for informed choice. Data does not demand fear. It demands attention. When attention is given early, outcomes change.

The future direction of security in the Southwest will not be decided by chance. It will be decided by whether early warnings are treated as noise or as guidance. History shows the cost of the wrong choice. Data now offers the chance to make the right one.

Idowu Ephraim Faleye is a data analyst and freelance writer, and the publisher of EphraimHill DataBlog, a platform dedicated to political analysis, public insights, and public policy commentary.

© 2025 EphraimHill DataBlog.

![The Trend of Insecurity in Nigeria. [Part 2]](https://ephraimhilldc.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Computer-Monitoring-of-Remote-areas.png)