[By Idowu Faleye- +2348132100608]

Nigeria’s political structure is a system of government that is undefined, drifting between federalism, unitary, and a loosely applied democratic framework. This inconsistent system is a critical reflection of Nigeria’s past and present political experiments aimed at managing its diverse ethnic and regional landscape.

To truly grasp Nigeria’s current political dilemma, one must journey through its history. The story begins long before independence. In 1914, the British amalgamated the Northern and Southern Protectorates, forming what we now know as Nigeria. In consideration of the diverse cultural and political differences among Nigeria’s ethnic groups, the British fostered regionalism, with each region governed based on its traditional structures.

Read Also: How Nigeria’s Stolen Wealth is Shaping Its Future

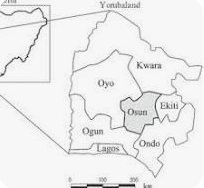

This regional autonomy set the stage for the federal system of government that Nigeria would later adopt. In the 1950s, regions were created to give each major ethnic group a degree of self-governance while maintaining national unity. Post-independence Nigeria adopted a federal structure with three regions—Hausa-Fulani in the North, Yoruba in the West, and Igbo in the East—each with substantial autonomy. Federalism was introduced in Nigeria as a tool to manage the country’s diversity.

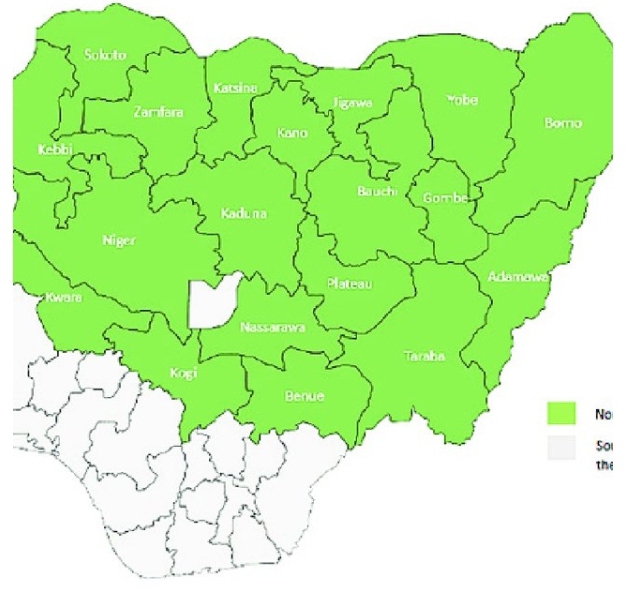

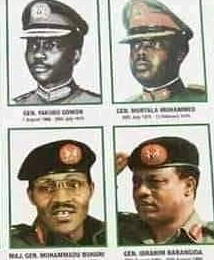

However, the military coups of the 1960s, beginning with the overthrow of the First Republic in 1966, drastically altered Nigeria’s political landscape. The military’s involvement in governance centralized power, leading to the creation of more states to weaken regional power, reduce ethnic tensions, and ensure control by the central government. Today, Nigeria has 36 states, and the federal system that was once designed to empower regions has become a centralized mechanism that stifles regional development and autonomy.

Nigeria’s brand of federalism is far from the textbook definition. In theory, federalism is a system where power is divided between a central authority and regional entities, allowing governance to be tailored to local needs while maintaining national cohesion. However, in practice, Nigeria’s federalism has been heavily centralized. The federal government holds substantial power and financial resources, creating an imbalance that leaves states overly dependent on federal allocations.

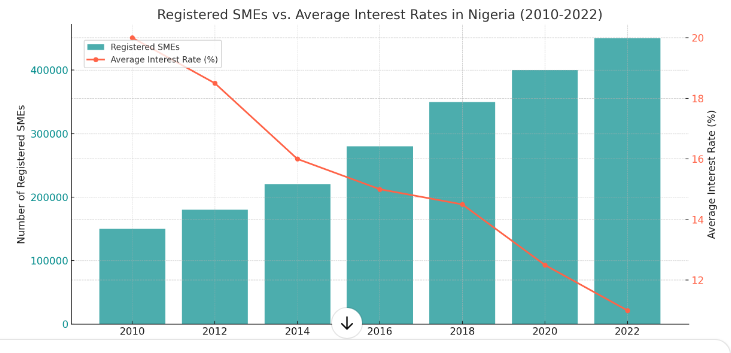

A 2022 report by the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) revealed that over 70% of state revenues come from federal allocations, with states like Bayelsa and Sokoto relying on these funds for more than 90% of their budgets. This overreliance undermines state autonomy, stifles innovation, and reduces the incentive for states to develop their own resources, leading to widespread economic stagnation.

The dependence on federal allocations has resulted in a cycle of underdevelopment. Many state governors have become mere administrators of federal allocations, rather than innovators or leaders driving local economic growth. The role of a governor in Nigeria has been reduced to receiving allocations, administering payments of salaries and pensions, awarding contracts, and overseeing procurement. There is little emphasis on developing the state’s own economy, and even less on long-term planning or innovation.

This situation has stifled economic growth, particularly in states that could have otherwise been economically viable if they harnessed their local resources. For example, a 2023 report by the Budget Office of the Federation showed that out of Nigeria’s 36 states, only Lagos and Rivers could generate more than 50% of their budgets through internally generated revenue (IGR). In contrast, states like Yobe and Ekiti generate less than 10% of their budgets from IGR, relying almost entirely on federal allocations.

This reliance on federal allocations has also led to a lack of accountability among state governments. The practice of “sharing the national cake” promotes a culture of entitlement, where states are more focused on securing their share of federal revenue than on fostering local innovation or economic growth. The result is a governance system that is reactive rather than proactive, with development projects often executed haphazardly based on the availability of federal funds rather than coherent, long-term plans.

For instance, despite Benue and Zamfara’s vast agricultural potential, they remain among the poorest states in the country due to minimal investment in agriculture and value-added industries. The inefficiency of this governance model is glaringly evident in the developmental stagnation across Nigeria. Unlike the regional governments of the past, which were responsible for significant economic contributions—such as the cocoa industry in the Western region or the groundnut pyramids in the North—today’s state governments do not mind replicating such successes.

Read Also: The Hidden Margins Between Politics and Governance in Nigeria

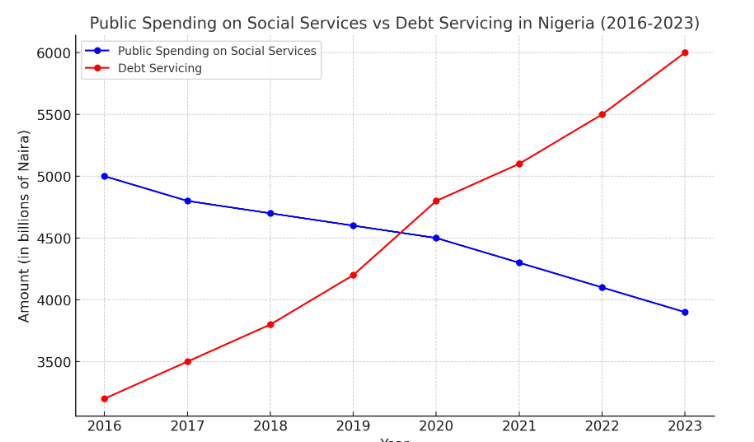

The lack of regional self-sufficiency has hindered national development, with states becoming increasingly dependent on a single source of revenue: oil. Furthermore, the over-centralization of resource management has deprived oil-producing regions, such as the Niger Delta, of the opportunity to develop their infrastructure and create jobs locally. Despite being the source of the country’s wealth, the Niger Delta remains one of the most underdeveloped regions in Nigeria. According to a report by the Nigeria Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (NEITI), over 80% of the population in the region lives below the poverty line, and environmental degradation from oil spills has devastated local livelihoods.

This centralization of resource management also led to absurdities, such as the location of oil refineries far from the Niger Delta, where the oil is extracted. The Kaduna refinery, situated in the northern region of Nigeria, is a prime example. It is a location that defies economic logic, as it is far removed from the oil-producing areas in the South-South region. This decision reflects a broader issue within Nigeria’s federal system, where resource control is concentrated in the hands of the central government, often to the detriment of the regions that actually produce these resources.

To address these challenges, Nigeria must consider a return to a true federal system of government, where power is more evenly distributed between the central government and the states. This would involve allowing states to control and manage the resources within their borders, enabling them to develop their own economies. For instance, Ekiti State could use its agricultural produce to earn money by trading with oil-producing states in the Niger Delta, which lack the fertile soil for farming. Each state should be encouraged to develop its own economic strengths, rather than relying on federal allocations.

Moreover, Nigeria should be divided along its six geopolitical zones—North Central, North East, North West, South East, South-South, and South West—with each zone having greater autonomy. This regional structure would allow for more tailored governance, where policies and development strategies are designed to meet the specific needs of each region. For example, the North West, with its large arable land, could focus on agriculture and become a breadbasket for the nation, while the South-South, with its oil resources, could invest in refining and petrochemicals.

Read Also: The Injustice of a Northern Presidency in 2027

This approach would not only promote economic diversification but also reduce the overreliance on oil, which has been the bane of Nigeria’s economy. It would also address the issue of resource control, where regions like the Niger Delta would have greater control over the management and benefits of their resources. This, in turn, would promote regional development and reduce the economic disparities that currently exist between Nigeria’s states.

In sum, the current system of government in Nigeria, with its over-centralization of power and resources, is unsustainable. It has stifled innovation, hindered regional development, and created a dependency culture that has left many states economically unviable. To achieve true development, Nigeria must embrace a system of government that allows for greater regional autonomy, where states are encouraged to develop their own resources and contribute to the national economy. This would not only promote economic diversification but also ensure that all regions of Nigeria benefit from the country’s wealth, leading to a more equitable and prosperous nation.

References:

Akinola, A. O. (2019). The Political Economy of the Nigerian Federalism: A Historical and Comparative Perspective. Springer.

Suberu, R. T. (2001). Federalism and Ethnic Conflict in Nigeria. United States Institute of Peace Press.

Diamond, L. (1988). Class, Ethnicity, and Democracy in Nigeria: The Failure of the First Republic. Syracuse University Press.

Mustapha, A. R. (2006). Ethnic Structure, Inequality and Governance of the Public Sector in Nigeria.

Ojo, E. O. (2009). Mechanisms of National Integration in a Multi-Ethnic Federal State:

Falola, T., & Heaton, M. M. (2008). A History of Nigeria. Cambridge University Press.

Nigeria Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (NEITI). (2023). Annual Report on the Petroleum Sector.

National Bureau of Statistics (NBS). (2022). Revenue Allocation and Economic Indicators Report.

Budget Office of the Federation. (2023). State Budgets and Internally Generated Revenue Report.

Nigeria Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (NEITI). (2021). Oil and Gas Industry Audit Report.

Born in Ekiti State, Nigeria, Idowu Faleye is a Policy Analyst and IBM-certified Data Analyst with an academic background in Public Administration. He’s the Lead Analyst at EphraimHill Data Consult and the Publisher of EphraimHill DataBlog, which posts regular topics on issues of public interest. He can be reached via WhatsApp at +2348132100608 or email at ephraimhill01@gmail.com

© 2024 EphraimHill DC. All rights reserved.This article is the intellectual property of EphraimHill DataBlog. For permission requests, please contact EphraimHill DC at ephraimhill01@gmail.com.

![The Trend of Insecurity in Nigeria. [Part 2]](https://ephraimhilldc.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Computer-Monitoring-of-Remote-areas.png)