[By Idowu Faleye: +2348132100608]

In African societies, the walls of prison do more than confine a person—they create a stigma so heavy that it follows the individual long after release, crushing hope and closing doors to a better future. What if prisons were more than just punishment centres? What if they prepared offenders for a life of purpose, free from crime, and gave them a genuine shot at redemption? For many ex-convicts in Africa, this remains a pipe dream. Instead, they emerge from incarceration shackled by a new kind of bondage: societal rejection, systemic neglect, and a dire lack of opportunities.

This isn’t just their problem—it’s ours. A society that fails to reintegrate its offenders is doomed to suffer the consequences of their inevitable relapse into crime. Alarmingly, in many African nations, recidivism rates exceed 50%. For instance, in Nigeria, over 70% of inmates are repeat offenders, a haunting reminder of a system that punishes but doesn’t reform. In Kenya, 47% of ex-offenders report insurmountable struggles to reintegrate, citing societal rejection and lack of employment opportunities as primary barriers. How did we get here, and more importantly, how do we break this vicious cycle?

Read Also:Mixing Different Categories of Offenders Behind Bars: The Urgent Case for Prison Reform.

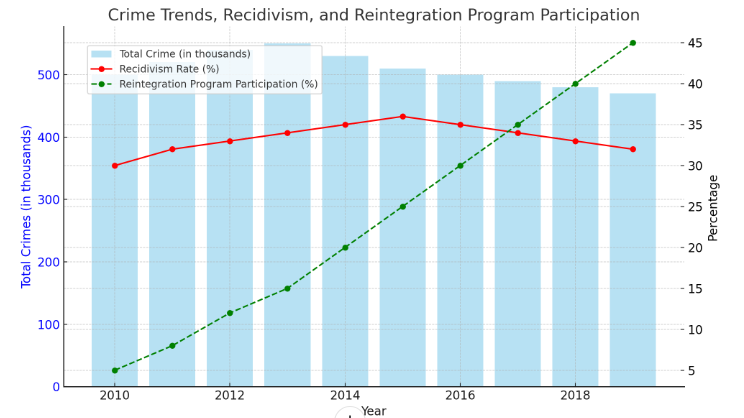

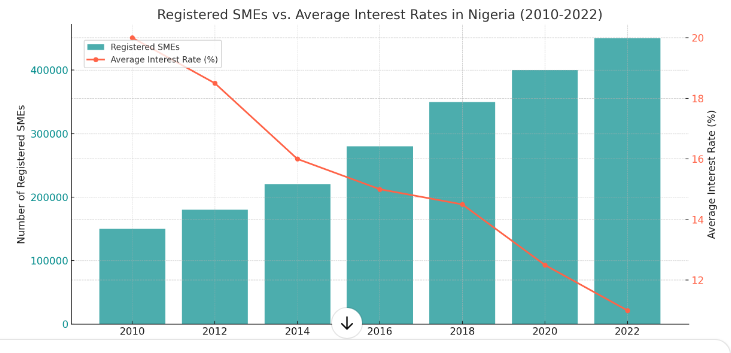

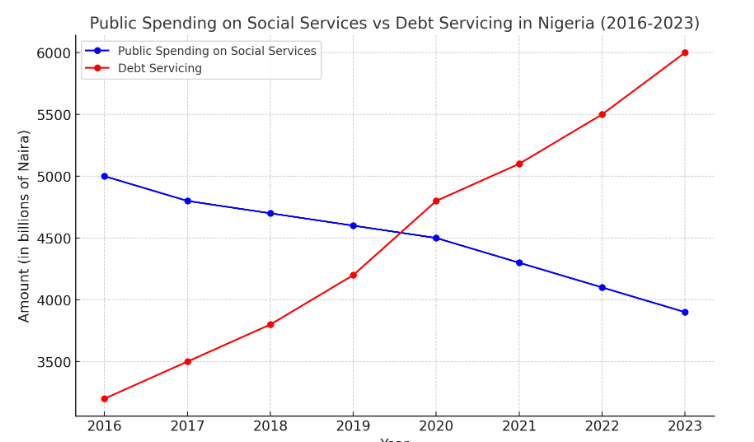

This chart illustrates trends in crime, recidivism rates, and participation in reintegration programs from 2010 to 2019:

Total Crimes (blue bars): Crime incidents have steadily decreased over the years, reflecting a downward trend.

Recidivism Rate (red line): After a slight increase between 2010 and 2015, the rate of recidivism begins to decline, possibly due to enhanced rehabilitation efforts.

Reintegration Program Participation (green dashed line): Participation in reintegration programs has increased significantly, indicating a growing focus on offender rehabilitation.

The visualisation highlights the importance of reintegration programs in reducing recidivism and improving societal outcomes

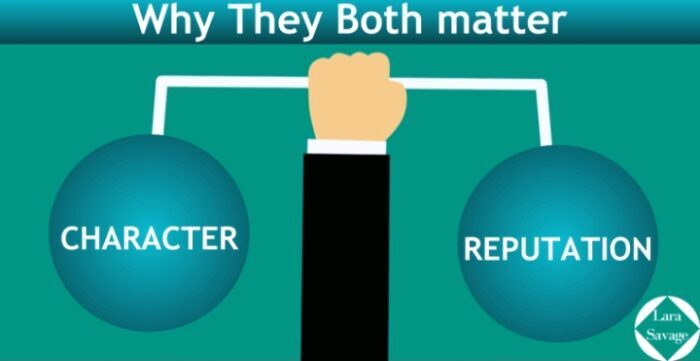

Read Also: Exploring the dichotomy between Character and Reputation

The principle of punishment is as old as humanity, but it was never meant to end with incarceration. Globally, modern justice systems recognise rehabilitation and reintegration as critical goals, yet these ideals often feel like an afterthought in Africa. Prisons—dubbed “correctional centres”—rarely live up to their name.

For ex-convicts, freedom often feels like a cruel joke. They leave prison only to face rejection from their families, ostracism from their communities, and outright discrimination from potential employers. The transition from inmate to law-abiding citizen is riddled with roadblocks, leaving many with no choice but to return to crime or, in despair, attempt to go back to the very prisons they once longed to escape.

Let’s put a face to the statistics. Meet Shola, a man once branded as a menace to society. During his years behind bars, Shola earned the title “prison president” for his leadership, conflict-resolution skills, and ability to maintain order among inmates. He was a model prisoner, respected by guards and inmates alike—a beacon of hope that people can change.

Yet, the world outside didn’t share this hope. Upon his release, Shola faced a community that labelled him a criminal beyond redemption. Employers turned him away. Old friends avoided him. Even his family treated him like a stranger.

The rejection weighed on him like a shroud until, in an act of desperation, Shola staged his re-arrest by slapping the local government chairman during a public event. To his surprise, the chairman chose not to punish him but instead listened. Recognizing Shola’s cry for help, the chairman offered him a job.

This act of empathy and inclusion transformed Shola’s life, proving that societal acceptance can be a powerful tool in breaking the cycle of recidivism. Shola’s story is rare, almost miraculous. For every Shola, there are countless others whose cries for help go unanswered.

The label of “ex-convict” is a scarlet letter, branding individuals as untrustworthy and unworthy of opportunity. Communities see them as ticking time bombs rather than as people who have paid their dues. A report by the African Centre for Justice and Peace Studies shows that over 70% of ex-convicts in sub-Saharan Africa experience severe discrimination upon release. This stigma isolates them, making it nearly impossible to secure employment, rebuild relationships, or find a place to belong.

Without societal acceptance, how can we expect ex-convicts to stay on the right path? In most African countries, governments fail to provide structured reintegration programs. Mental health counselling, vocational training, transitional housing—these lifelines are either non-existent or woefully inadequate. Without them, ex-convicts are left to navigate the challenges of reintegration alone.

Compare this to Norway, where rehabilitation is prioritized, and recidivism rates hover around 20%. Why? Because inmates leave prison equipped with skills, education, and a support system. Africa’s failure to adopt such models is a glaring oversight.

Isolation and rejection often drive ex-convicts back to crime. Prisons, ironically, serve as breeding grounds for criminal expertise, and without alternatives, released prisoners revert to what they know best. The African Journal of Criminology reports recidivism rates exceeding 50% in some African nations. These are not just numbers—they represent lives lost to a broken system and communities destabilized by its failures.

Ignoring the reintegration of ex-convicts is not just cruel; it’s costly. High recidivism rates lead to overcrowded prisons, strained public resources, and increased crime rates. Take Nigeria as an example: the Nigerian Correctional Service reports that over 70% of inmates are repeat offenders. This statistic isn’t just a failure of the justice system; it’s a failure of society as a whole. Inaction perpetuates a cycle that harms everyone—ex-convicts, their families, and their communities.

Shola’s story offers a blueprint for change. His transformation began with one person’s decision to see him as more than his past. Imagine the impact if entire communities and governments adopted this approach.

Understanding the root causes of crime—poverty, lack of education, social exclusion—can shift societal attitudes. Empathy can replace judgment, creating an environment where ex-convicts are given the support, they need to rebuild their lives.

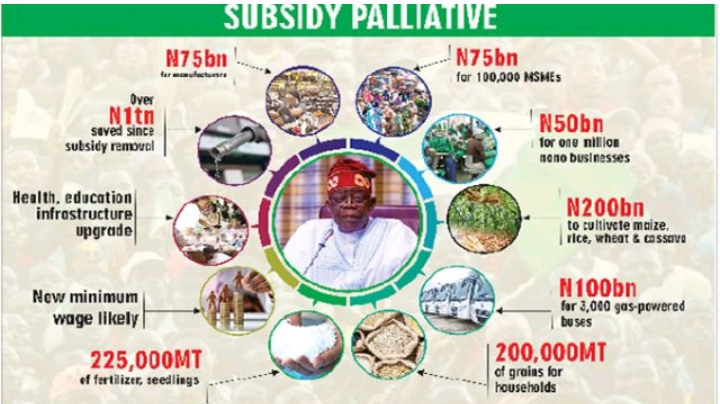

Governments must prioritize reintegration. Vocational training, mental health counselling, transitional housing, and mentorship programs that can equip ex-convicts with the tools they need to succeed. In Ethiopia, community-based integration initiatives have shown promise, reduced stigma and enhanced employability among ex-offenders.

Change begins at the grassroots level. Communities must be educated about the dangers of ostracizing ex-convicts. Support networks, such as peer groups and reintegration workshops, can foster a sense of belonging and accountability.

Policies should safeguard ex-convicts from discrimination in employment, housing, and social services. Justice systems must shift their focus from punishment to rehabilitation, emphasizing education, skill-building, and mental health support during incarceration.

Read Also: The Hard Way is the Only Way for Sustainable Economic Recovery in Nigeria

Reintegrating ex-convicts is not just an act of compassion—it’s a necessity for safer, more inclusive societies. Governments, communities, and individuals all have roles to play. Governments must invest in robust reintegration programs and reform justice systems to prioritize rehabilitation.

Communities must shed the stigma that isolates and ostracizes, embracing ex-convicts as individuals capable of change. Individuals must choose empathy over judgment, understanding that every second chance is an opportunity to rebuild lives and strengthen society.

Read Also:Buhari’s Untouchable Past: The Lingering Legacy of Resources Mismanagement in Nigeria

Shola’s redemption began with one person’s belief in his potential. Imagine the ripple effect if every ex-convict were given the same opportunity. We have the power to transform prisons from punitive institutions into true correctional centres, to turn rejection into acceptance, and to break the cycle of recidivism once and for all.

The question is not whether ex-convicts deserve a second chance. The question is whether we, as a society, are willing to give it to them. Let’s rewrite their stories—and ours—together.

References:

African Centre for Justice and Peace Studies.

African Journal of Criminology (2022).

SCIELO, IJSSHR, and the National Re-entry Resource Centre report on recidivism and reintegration globally.

Nigerian Correctional Service statistics on repeat offenders.

Idowu Faleye:Ekiti-born Policy Analyst, IBM-certified Data Analyst, and Lead Analyst at EphraimHill Data Consult. Publisher of EphraimHill DataBlog, addressing topics of public interest. Reach him via WhatsApp at +2348132100608 or email ephraimhill01@gmail.com.

© 2024 EphraimHill DC. All rights reserved.

![The Trend of Insecurity in Nigeria. [Part 2]](https://ephraimhilldc.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Computer-Monitoring-of-Remote-areas.png)