Written By Idowu Ephraim Faleye – 08132100608

Kidnapping has become a national emergency in Nigeria. It is no longer confined to the wealthy, the politically connected, or the privileged few. Today, it is the ordinary Nigerian students in the classrooms, farmers tilling the soil, traders hawking goods, commuters crammed in buses, and even children playing in the courtyards—who live under the shadow of abduction. From the cities to the villages, from highways lined with checkpoints to farmlands, no corner of the nation is spared. Every step outside one’s home carries the weight of uncertainty: Will I return? Will my child be snatched? Will today be the day the unthinkable becomes a reality?

What is most unsettling is not just the frequency of these incidents, but the brazen ease with which they are carried out. The streets are no longer safe. Bush paths, once shortcuts to kinship and commerce, have become trails of terror. Even the four walls of a home, once a sanctuary, offer no guarantee of protection. Yet, amid this suffocating fear, the Nigerian government’s response remains detached from the intensity and urgency that such a grave national crisis demands. While other crimes are tragic and costly, kidnapping, by its nature, is deeply traumatic. It strikes at the heart of our shared humanity—ripping children from their mothers, fathers from their families, and hope from their communities.

Read Also: Governor Fayemi’s Abandoned Projects and the Cost of Ambition

To fully grasp the scale of what we now face, it’s essential to understand the progression of crime in Nigeria. After the civil war of the late 1960s, Nigeria entered an era dominated by brazen armed robbery. Leftover weapons from battlefields found new purpose in the hands of highway bandits. The name Oyelusi became synonymous with terror. As we moved into the late ’80s and early ’90s, criminals shifted toward more organized and sophisticated operations. Figures like Lawrence Anini and Monday Osunbor orchestrated bank robberies with military precision, their operations fueled by insider tips and corrupt alliances.

Then came the era of financial deception. The early ’90s saw the rise of fraudulent finance houses promising impossibly high returns. Innocent Nigerians, eager for prosperity, lost their life savings to schemes organized by the likes of Owolabi and Nmana-Nmana. Although the legal framework had yet to catch up, these scams would later be categorized under Section 419 of the Criminal Code. Then came the digital age, and with it, a new breed of criminal. Tech-savvy youths—especially the unemployed—found an outlet in cybercrime. What began with fake romance scams quickly grew into sophisticated hacking networks and phishing schemes. Some of these fraudsters even secured insider support from bank employees who sold customer data and provided cover.

As the country embraced a cashless economy, traditional crimes like burglary and armed robbery reduced drastically, but criminals simply adapted. Point-of-sale (POS) operators became the new soft targets. Their locations were easy to trace, their earnings were in cash, and their security was almost non-existent. These shifts in crime types, though dangerous in their own right, are soft in comparison to the monster we now face—kidnapping. It has overtaken every other crime in frequency, brutality, and emotional cost. Unlike cybercrime or robbery, kidnapping involves human beings—real people torn from their lives and dignity, tortured physically and psychologically, and then exchanged for ransom-like items in a marketplace.

Its rise can be traced to the arrest of Chukwudi “Evans” Onuamadike in 2017, who gave Nigerians a peek into the dark world of organized abduction. Evans had built a criminal empire through meticulously planned kidnappings, often demanding ransoms of ₦100 million and above. His confession confirmed what many feared: kidnapping was no longer a desperate act by armed thugs; it was a calculated business, far more profitable and less risky than armed robbery or cybercrime.

Kidnapping succeeds not just because of its profitability, but because of a system that inadvertently supports it. The laws are weak and inconsistently enforced. The risk of capture is low, and even when arrests are made, convictions are rare. Families are left with no choice but to comply with ransom demands. Police often delay action, fearing the death of hostages, which gives the criminals more time to retreat and regroup.

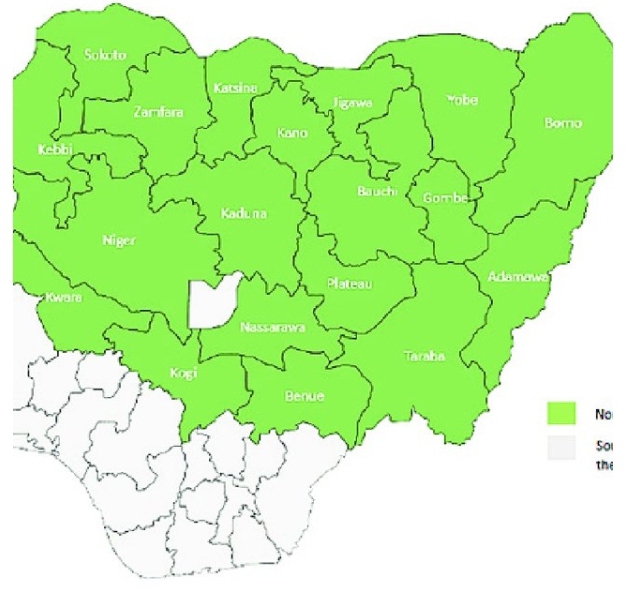

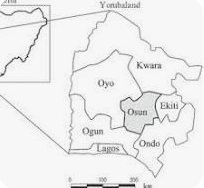

Today, kidnapping in Nigeria manifests in various terrifying forms. In the forests and farmlands of the North Central and Southern zone, nomadic Fulani herdsmen—many of who are undocumented migrants from Niger, Chad, and Cameroon—have turned the forests into hunting grounds and have weaponized it. Armed with AK-47s and ancestral grudges, they operate in bands, ambush vehicles, and march victims into deep forests where they set their wilderness camps. They seek no particular target—anyone is a source of income. Their demands are harsh, their tactics brutal, and their connections far-reaching. A 2022 SBM Intelligence report paints a harrowing picture: over 3,000 Nigerians were kidnapped in a single year, and their fates bartered over crackling phone lines.

Urban syndicates, on the other hand, operate with clinical efficiency. Often comprised of ex-fraudsters and ex-robbers, these groups monitor high-net-worth individuals, obtain insider information, and execute snatch-and-hide operations from rented buildings within the cities. But the darkest evolution is the rise of “Yahoo Plus” rituals—a macabre fusion of cybercrime and occultism where some cybercriminals are now transitioning into physical kidnapping, in which victims are sacrificed for spiritual wealth. This is not folklore; it is the reality in many parts of the Southern zone, where body parts fetch higher prices than ransom.

Even more chilling is the booming black market for human organs. Across Nigeria, criminal networks steal human beings, not just for ransom, but for parts. Organ harvesters collaborate with rogue doctors and commercial drivers. Passengers are sedated with sleeping drugs, diverted to forest camps, and dismembered like animals. Numerous survivors have narrated tales of dozing off in buses only to be awakened, tied and drugged in unknown locations. Kidnappers also target children for illegal adoption, trafficking, or are murdered for their vital organs and body parts or ritual use. In some cases, graves are dug up. In both cities and villages, body part merchants and ritual killers now operate with near impunity. The message is clear: in Nigeria, even the dead are not safe

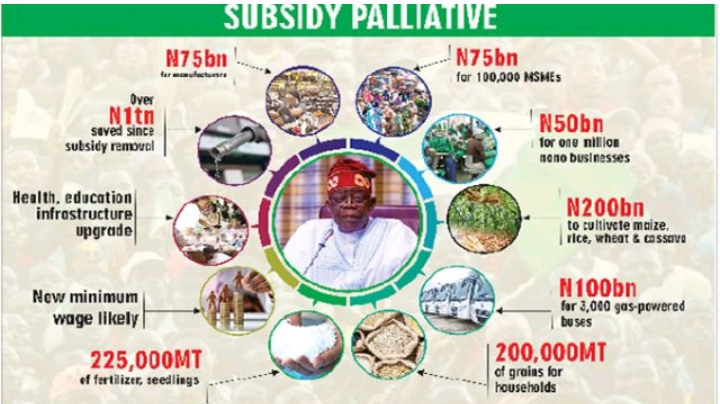

Still, the security system remains slow, outdated, and in some cases, indifferent. Law enforcement agencies possess the tools for modern surveillance—telecom data, crime databases, and even access to Nigeria’s satellite systems—but rarely use them effectively. Our intelligence agencies are limited not by lack of resources, but by lack of capacity and accountability. Satellites like NigerSat-1 and Sat-X could be deployed to scan hideouts in forests, but remain idle. The removal of fuel subsidies reportedly saved the country over ₦1.5 trillion in 2023. Even a fraction of this could revolutionize surveillance and policing.

Read Also: Locked Out After Lockup: The Untold Struggles of Ex-Convicts in Africa

Banks and telecommunications companies also have roles to play. Most ransom payments involve the use of mobile phones, yet criminals continue to operate with fake or pre-registered SIM cards. Regulatory bodies are either overwhelmed or complicit. When ransoms are paid in cash, they often re-enter the banking system through deposits, transfers, or shell accounts. A responsive interbank alert system, connected to law enforcement and the Nigeria Financial Intelligence Unit, could trace these transactions and help dismantle these syndicates.

The people who commit these crimes do not live in the forest forever. They mingle with us, buy food in our markets, treat wounds at local clinics, and boast in coded language about their exploits. With a functional community surveillance structure and robust whistleblower protections, many could be unmasked. But fear, corruption, and public distrust have silenced many who could have spoken out.

The Nigerian government cannot continue to treat kidnapping as a side issue. It has become a national security emergency. It is no longer confined to a region, class, or context. The ripple effects are everywhere. Farmers are abandoning their land. School children are dropping out in the North. Rural dwellers are migrating to already congested urban centers. Businesses are closing early, and citizens are living in anxiety and trauma.

This is more than a crime—it is war. A war on education. A war on commerce. A war on food security. A war on human dignity and national unity. It is disrupting our economy, distorting our way of life, and endangering future generations. Every Nigerian knows someone who has been kidnapped—or fears being next. For every victim who returns, there are families permanently scarred, bank accounts emptied, and hopes shattered.

This situation requires bold, visionary, and data-driven solutions from the leadership. The era of excuses is over. The Nigerian government must now rise to defend its citizens, not just with weapons. Nigeria needs a security overhaul: intelligence-driven policing with surveillance, swift prosecutions, and modernized laws, accompanied by a collective sense of urgency. This is a clarion call to action—a demand for a nation where children play without fear, farmers reap their harvests, and roads lead to hope, not horror. In the face of this suffering, silence is complicity, inaction is betrayal, and delay is death.

Idowu Faleye is the founder and publisher of EphraimHill DataBlog, a platform committed to Data Journalism and Policy Analysis. With a strong background in Public administration and Data Analytics, his articles offer research-driven insights on Politics, governance and Public Service delivery.

![The Trend of Insecurity in Nigeria. [Part 2]](https://ephraimhilldc.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Computer-Monitoring-of-Remote-areas.png)