Written By Idowu Ephraim Faleye – 08132100608

Nigeria’s prison system, despite its rebranding as the Nigeria Correctional Service, remains a stark symbol of systemic failure, manifest by overcrowding, decaying infrastructure, and a glaring absence of meaningful rehabilitation. Imagine stepping into a crowded room where you can barely breathe, where the air is thick with despair, and the hope of leaving the place is a distant memory. This is the daily reality for almost 80,000 individuals crammed into Nigeria’s correctional facilities.

The Nigerian Prison custody nationwide was initially built to house approximately 64,192 inmates. Yet, as of March 2024, these facilities held 78,519 individuals, pushing them far beyond their intended capacity. This severe overcrowding isn’t just a statistic; it’s a breeding ground for disease, violence, and psychological trauma. Imagine being confined to a space meant for one person but shared with three others, with inadequate ventilation and sanitation. This is the grim reality for many inmates.

Perhaps the most heart-wrenching aspect is that nearly 70% of these inmates are awaiting trial. Some have been incarcerated for over a decade without a court hearing, while the rest serve sentences under conditions that neither reform behavior nor foster reintegration into society. This prolonged detention without trial not only violates their fundamental human rights but also erodes their faith in the justice system.

Read Also: There’s Silent War in The forests of Yorubaland: Rise Before Our land Falls

Many are accused of minor offenses, yet they endure the same harsh conditions as those convicted of serious crimes. The psychological toll is immeasurable, leading some to lose hope entirely. These aren’t just numbers; they represent real people with families, dreams, and untold stories. This dysfunction not only perpetuates cycles of criminality but also poses significant threats to justice and public safety.

To understand the roots of this crisis, it is essential to revisit history. Nigeria’s prison system began in 1861 with the establishment of Western-style prisons. Over 160 years later, the system groans under the strain of severe overcrowding. Most of Nigeria’s prisons were constructed during the colonial era and have seen little to no renovation since. The Suleja Custodial Centre, for instance, built in 1914 to house 250 inmates, now holds nearly double that number. In April 2024, heavy rains caused the perimeter fence to collapse, allowing 119 inmates to escape back to continue tormenting society. Such incidents underscore the urgent need for infrastructural overhaul. Dilapidated facilities not only compromise security but also dehumanize those within.

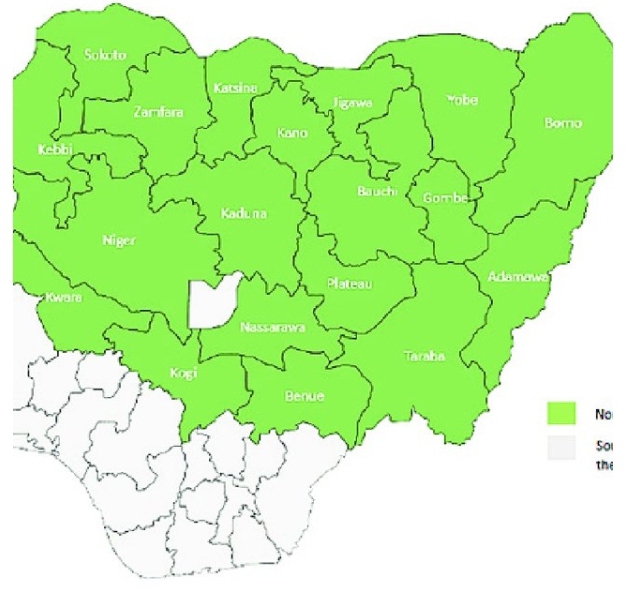

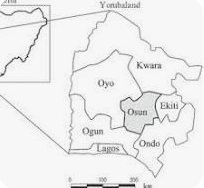

Most of the prisons built during colonial times are now crumbling. Another example is Kirikiri Maximum Security Prison, built in 1955 for 1,056 inmates, now holds more than 3,000. Cells lack ventilation and proper sanitation, encouraging disease and unrest. As of 2016, prisons in Southern Nigeria were operating at an alarming 81% over capacity, exacerbating inhumane conditions and overstretching already fragile infrastructure. This decay stems from decades of abandonment. Nigeria’s correctional facilities suffer from aging infrastructure, insufficient personnel, and collapsing standards. Between September 2015 and July 2023, at least 17 jailbreaks occurred, leading to over 7,000 escapees—clear evidence of rising security risks linked to congestion.

Read Also: Kidnapping in Nigeria: A National Emergency That Demands Immediate Action

Compounding the crisis is the issue of death row inmates and the unwillingness of state governors to carry out lawful executions. Granting capital punishment is legally sanctioned for certain crimes, but Nigerian governors, who are authorized to sign execution warrants, often refuse to do so, citing personal ethics, public opposition, or political indecision. As of December 2024, Amnesty International reports that there were 3,569 individuals on death row in Nigeria—the highest number in Sub-Saharan Africa.

The reluctance of state governors to sign execution warrants has left these individuals in a perpetual state of limbo. These inmates remain trapped in a state of suspended torment, and this indecision contributes significantly to overcrowding and places additional strain on already scarce resources. Imagine living each day uncertain if it will be your last, trapped in a cycle of endless waiting.

Sadly, Inmates serving terms for minor offenses are often housed with hardened criminals, creating a breeding ground for criminal networking. Prisons, in effect, become innovative schools for crime. Many young men enter for petty theft and exit more dangerous, having endured violence, gang indoctrination, and survivalist mentalities. With one in four former inmates re-arrested within a year, recidivism in Nigeria remains alarmingly high.

Read Also:Governor Fayemi’s Abandoned Projects and the Cost of Ambition

In addition to poor classification and overcrowding, corruption among prison staff worsens the plight of inmates. Reports abound of wardens diverting food funds, leaving inmates with barely edible meals. Basic medical care is frequently unavailable. Although the government increased daily feeding allowances in 2023, the amount remains insufficient for a healthy diet. Also, reports of prison officials colluding with inmates to run drug rings, or even committing crimes outside the prison walls in complicity with the prison wardens, are not uncommon. When those entrusted with rehabilitation become complicit in criminal activities, it erodes trust and perpetuates a cycle of crime.

Equally troubling is what awaits prisoners upon release. Many ex-convicts return to society and find themselves ostracized by a society that stigmatizes and rejects them. The lack of structured reintegration programs leaves ex-convicts without the support needed to rebuild their lives after completion of their prison term. Discrimination in employment, housing bans, and social exclusion leave many with limited options to rebuild their lives, and they have no choice but to return to crime. Thus, the cycle of incarceration continues, fuelled not by criminal intent alone but by systemic failure and societal neglect.

Nevertheless, meaningful reforms are possible. The first step must be the proper classification of inmates based on the severity of their crimes. Separating violent offenders from nonviolent ones can curb the spread of criminal ideologies within prison walls. Additionally, the government must prioritize the construction of modern, secure, and humane correctional facilities.

Alongside structural reform, rehabilitation programs are essential. Vocational training in areas such as agriculture, craftsmanship, and public works can equip inmates with marketable skills. Studies show that participation in correctional education reduces recidivism by up to 43%. Thus, these programs not only restore dignity but also prepare inmates for successful reintegration.

To support this shift, prison staff must be retrained. Officials with punitive mindsets should be replaced with professionals committed to rehabilitation. New personnel should be equipped with training that emphasizes the correctional mandate of reform rather than punishment.

Equally important is the role of state governors. They must fulfill their constitutional obligations regarding capital punishment. Addressing the backlog of death row inmates—either through lawful execution or sentence commutation—is necessary to reduce overcrowding and ensure justice is neither delayed nor denied. Avoiding this duty does not abolish the death penalty; it only deepens the chaos.

Read Also: Exploring the dichotomy between Character and Reputation

Ultimately, the tragedy of Nigeria’s prison system lies not only in its physical decay but in its betrayal of justice. Each statistic represents a human story: a son awaiting trial for years, a mother condemned but never executed, and a youth hardened by incarceration rather than reformed by discipline. When we call these institutions “correctional centers,” we must ask what, if anything, they correct.

The term “correctional facility” implies a focus on reform and rehabilitation. However, rehabilitation within Nigerian prisons is largely non-existent. The environment is punitive rather than reformative. The term “correctional center” has become a misnomer—now synonymous with abuse, deprivation, and squandered human potential.

However, there have been signs of progress recently. The Ministry of Interior, under Hon. Dr. Olubunmi Tunji-Ojo, has initiated reforms aimed at improving inmate welfare and rehabilitation. Showrooms displaying products made by inmates have been established, showcasing their potential and providing a sense of purpose. International collaborations with organizations like the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime have further bolstered these efforts.

Read also: Mixing Different Categories of Offenders Behind Bars: The Urgent Case for Prison Reform.

Additionally, the government has increased the daily feeding allowance for inmates to N1,125, ensuring better nutrition. Renovations of facilities, such as the Medium Security Custodial Centre in Kuje, have introduced improved living conditions, aligning with global standards. These steps, though commendable, are just the beginning of a long journey toward comprehensive reform.

The challenges facing Nigeria’s prison system are monumental, but they are not insurmountable. It requires a concerted effort from the government, civil society, and the international community. Legislative reforms to expedite trials, infrastructural investments, and the implementation of rehabilitation programs are critical. Moreover, addressing corruption within the system is paramount.

Until Nigerian leaders find the courage to implement bold reforms and society begins to treat ex-offenders as individuals worthy of a second chance, the cycle of crime and incarceration will continue. Change must begin now, not tomorrow, not next election cycle. Each day of delay deepens the damage, adds to the suffering, and weakens a system we can no longer afford to ignore.

Reflectively, the current state of Nigeria’s prison system reflects broader governmental and societal negligence. Without urgent and comprehensive reform, the cycle of crime, imprisonment, and recidivism will persist, undermining justice, endangering public safety, and wasting human lives.

Idowu Faleye is the founder and publisher of EphraimHill DataBlog, a platform committed to Data Journalism and Policy Analysis. With a strong background in Public administration and Data Analytics, his articles offer research-driven insights on Politics, governance and Public Service delivery

![The Trend of Insecurity in Nigeria. [Part 2]](https://ephraimhilldc.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Computer-Monitoring-of-Remote-areas.png)