By Idowu Ephraim Faleye +2348132100608

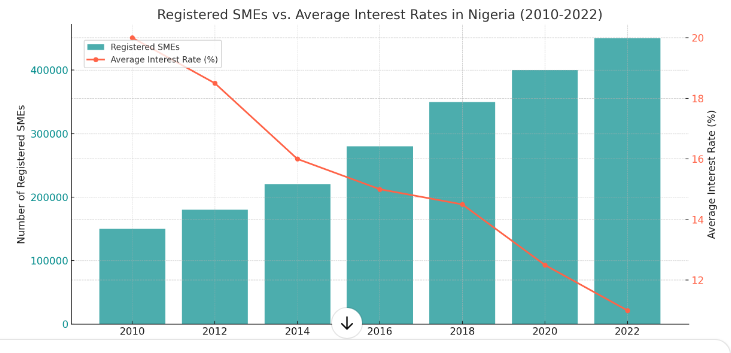

Early warning signs in security data rarely announce themselves through a single dramatic incident; they emerge quietly through patterns. Repetition of similar attacks, their geographic concentration, timing, and the consistent choice of targets form measurable signals that point to deeper security trends. While an isolated event can be dismissed as a random crime, a sequence of related incidents occurring under comparable conditions becomes actionable data. When examined through a data-driven lens, these emerging security patterns often reveal risks and trajectories far earlier—and more accurately—than official statements or reactive public discourse

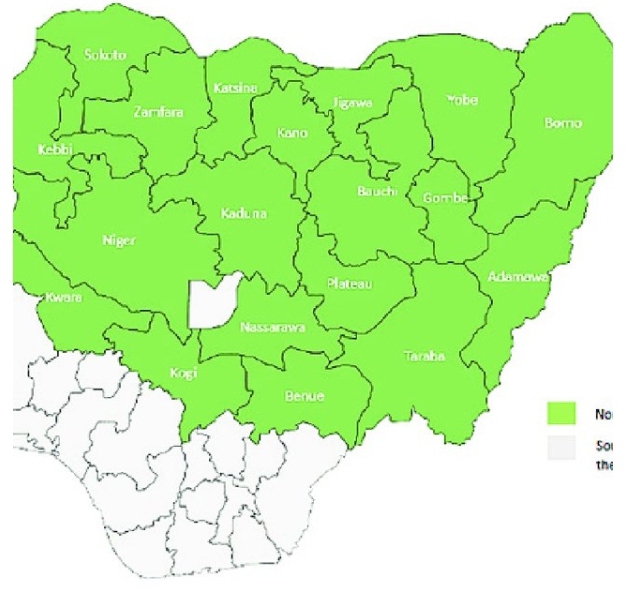

From an analytical standpoint, recent attacks in parts of the Southwest should not be viewed as random or disconnected. When examined together, they reveal consistent patterns that point to the movement, adaptation, and early-stage consolidation by armed groups. This assessment is based on observable incidents, open-source intelligence, security alerts, geographic clustering, and post-disruption behaviors following counterterrorism operations in Northern Nigeria.

Read Also: A Wake-Up Call to the Newly Constituted South West Development Commission

One of the most consistent patterns is target selection. Recent attacks have shown a clear focus on locations where weapons can be accessed or seized. Police facilities, security outposts, and areas linked to arms control have been disproportionately affected. This is a critical indicator. Groups that already possess sufficient weapons tend to avoid confrontation with armed institutions. Groups that lack arms or are rebuilding capacity actively seek them. From a data perspective, this pattern strongly suggests a rearmament phase rather than a full operational phase.

Timing further strengthens this interpretation. The sudden increase in security incidents in the Southwest follows intensified military and allied actions against terrorist networks in the North and across the Sahel corridor. According to official statements, the United States strikes in Nigeria targeted Islamic State elements moving from the Sahel to support the Lakurawa jihadist group and bandit networks. These militants reportedly provided training, logistics, and operational support. The Islamic State Sahel Province is already active in Niger, Burkina Faso, and Mali, where it has sustained a violent insurgency. Pressure in those regions has disrupted established networks and forced elements to seek alternative spaces.

Disruption rarely ends a threat. It redistributes it. Armed groups under pressure fragment, move in smaller units, and seek regions with weaker surveillance and more permissive terrain. The data suggests that parts of the Southwest have become such spaces. This is not because the region is inherently weak, but because its forests, rural corridors, and interstate routes remain difficult to monitor using conventional security methods.

Read Also: Saving Yorubaland from Fulani Invasion Before It’s Too Late

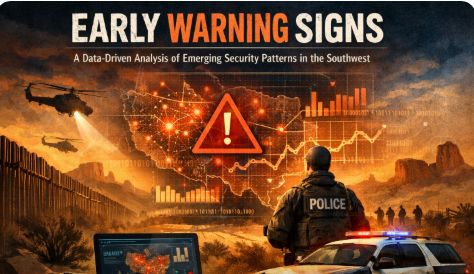

Geography plays a decisive role in this pattern. Many recent incidents have occurred in or around forest-adjacent communities. Forests provide concealment, logistical cover, and escape routes. They also allow armed actors to observe communities and security responses before acting. Locations such as the Benin–Owo–Ipele corridor illustrate this risk clearly. It is a strategic inter-state route cutting through forested terrain with multiple exit paths. Criminal and terror-linked networks understand terrain well. They exploit areas where control is fragmented and response times are slow.

This geographic factor was evident in the attack on the Ipele Divisional Police Headquarters in Ondo State on 31 December 2025. The choice of location aligns with forest proximity and route accessibility. Similarly, the attack at NPS Oloka in Orire Local Government Area of Oyo State on the night of 6 January raised long-standing concerns among residents. Community leaders openly referenced their vulnerability due to surrounding forest settlements and unregulated movement. These concerns are not speculative; they align with known risk indicators in conflict analysis.

Migration data adds another layer of insight. Reports of intercepted individuals moving from Northern states into forested areas of the Southwest cannot be dismissed when viewed alongside rising attacks. The Ondo State Amotekun Corps’ arrest of 61 suspicious migrants in the Elegbeka forest between Ifon and Akure is a concrete example. Preliminary profiling indicated that some of the suspects came from Sokoto and Kano and intended to settle in the forest. This is evidence of mass migration of displaced terrorists, and a red flag when such movements intersect with known attack patterns and geographic risk zones.

Intelligence reporting supports these observations. On 22 October 2025, a leaked security alert from the Department of State Services warned of planned coordinated attacks by the Islamic State West Africa Province. While Ondo state officials described the memo as routine intelligence sharing, they also confirmed it was used to assess threats and guide proactive measures. This confirms that security agencies are seeing indicators consistent with broader movement and coordination, not isolated crimes.

Read Also: Kidnapping in Nigeria: A National Emergency That Demands Immediate Action

When these elements are analyzed together, a clear inference emerges. Armed groups affected by operations in the North and Sahel have been weakened but not eliminated. Leadership disruption and territorial losses have forced surviving elements into a phase of relocation and rebuilding. The Southwest, with its forest cover and strategic corridors, has become part of that adaptive movement.

Crucially, the data suggests these groups are not yet fully armed or operational in the region. Their actions point to preparation rather than execution. Targeting weapon sources, settling quietly in forests, and avoiding sustained engagements are all behaviours associated with early-stage consolidation. From a risk analysis perspective, this is the most important finding. It means the threat is real, but it is not yet mature.

This stage presents both danger and opportunity. Danger, because inaction allows for consolidation. Opportunity, because early intervention is significantly more effective and less costly than a late-stage response. Many security failures occur not because threats were invisible, but because early signals were not acted upon decisively.

Another analytical concern is the limitation of current response models. Routine patrols and reactive deployments are not designed for forest-based threats. Road checkpoints do not control bush routes. Post-incident raids often arrive after attackers have withdrawn into cover. This creates a cycle of response without prevention, which favors mobile and adaptive groups.

Modern threats such as kidnapping, organized violent crime, and terror-linked activity require intelligence-led operations. Surveillance, early detection, and continuous monitoring are more effective than static defenses. From a data-driven perspective, the absence of persistent visibility over forest spaces remains the most critical gap.

This is where technology becomes central to any credible prevention strategy. Surveillance drones provide scalable coverage over difficult terrain. They can identify unusual movement patterns, temporary camps, and emerging routes without exposing personnel to unnecessary risk. When integrated with ground intelligence and inter-agency coordination, they shift security posture from reactive to anticipatory.

The recommendation to invest in drone surveillance is not based on theory. It directly responds to the identified pattern: forest-based movement, early-stage settlement, and weapon-seeking behavior. Securing and regulating these spaces early prevents criminal consolidation. Delayed action allows armed groups to entrench, recruit, and rearm, at which point disruption becomes far more costly.

Coordination is equally important. Forests and corridors cut across state boundaries. Fragmented responses create exploitable gaps. Intelligence sharing, joint surveillance, and regional planning are essential. Armed groups operate as networks; responses must do the same.

This analysis does not claim access to classified intelligence. It is based on observable incidents, geographic clustering, open-source reports, and known post-disruption behavior of armed groups. Within these limits, the signals are consistent and concerning.

The current phase should be understood clearly. The threat is present, mobile, and adaptive, but not yet consolidated. That window will not remain open indefinitely. As history shows, groups that are allowed time and space eventually stabilize, arm themselves, and escalate operations.

Data does not predict the future with certainty, but it does indicate direction. Currently, the direction suggests that without early, intelligence-led intervention, the Southwest may face a more organised and violent phase of insecurity. Acting early changes that trajectory.

From an analytical standpoint, the evidence suggests a straightforward conclusion: early visibility, early disruption, and coordinated action yield the highest return on security investment. Waiting for larger attacks only confirms what the data is already warning about.

Idowu Ephraim Faleye is a data analyst and freelance writer, and the publisher of EphraimHill DataBlog, a platform dedicated to political analysis, public insights, and public policy commentary.

© 2025 EphraimHill DataBlog.

![The Trend of Insecurity in Nigeria. [Part 2]](https://ephraimhilldc.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Computer-Monitoring-of-Remote-areas.png)