[By Idowu Faleye: +2348132100608]

Imagine a project meant to uplift the education of young Ekiti-State children—a new school building, built to provide a safe learning space for students. Yet, within just four years, defects appear and structural issues arise. That’s the situation with Ayo Fasanmi Model College in Ado-Ekiti, a school built by contractors and supervised by civil servants using public funds. Now, the school stands in disrepair, closed by the government in the name of student safety. This painful truth forces us to confront an uncomfortable question: Where do we place the blame for Poor Service Delivery in Nigeria?

As the government steps up to renovate the building and prioritize student safety, citizens are left asking who allowed this breakdown in quality to happen in the first place. This isn’t just about one school; it’s a mirror reflecting a larger, disturbing pattern across the nation. In Ekiti State, projects funded by public money crumble within a few years, often a direct consequence of poor oversight and mismanagement. While politicians make promises, it’s Nigeria’s civil servants who implement them—or sabotage them. So, if we’re truly serious about change, let’s delve into the structural issues that let these failures happen repeatedly.

Nigeria’s civil service system was initially designed as a backbone for national progress, implementing policies and projects that would foster growth and improve lives. But as years have passed, that original purpose seems to have eroded. What was meant to be a tool for good has, instead, become a machine of bureaucracy, corruption, and inefficiency that contributes to the country’s economic stagnation.

Civil servants are the ones who advise politicians on budgets, oversee projects, and manage the day-to-day workings of government-funded programs. Yet, it’s no secret that many civil servants work to inflate project costs, approve substandard work, and manipulate budgets for personal gain. Take the Ayo Fasanmi Model College as an example. The school was meant to be a safe place for learning, constructed with government-prescribed standards. However, the involvement of civil servants in supervising the project didn’t prevent the shoddy execution that has now forced students out of classrooms.

It’s not just Ekiti State—this story repeats itself nationwide. Civil servants hold significant power in Nigeria’s governance, but many have used that power to prioritize personal gain over public good. Through corrupt alliances with contractors and politicians, many have transformed public offices into vehicles for wealth accumulation rather than public service. And this isn’t happening in the shadows; it’s an open secret.

Read also: Nigeria’s Masses Struggle with Inequality and Exclusion from the Nation’s Commonwealth.

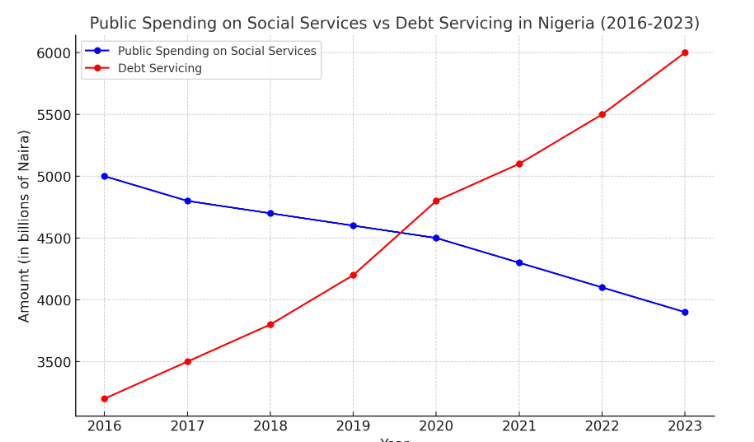

Civil service corruption has ripple effects that extend far beyond the immediate project. When funds are mismanaged, and projects fail, it’s the citizens who bear the brunt of these failures. Infrastructure projects that were supposed to bring roads, schools, and hospitals to underserved areas end up being abandoned or collapsing soon after completion. Public trust in government institutions is eroded, and citizens lose hope in the system that’s supposed to work for them.

Statistics paint a bleak picture. Nigeria loses an estimated $18 billion annually to corruption, with a significant portion tied directly to civil service inefficiencies and financial mismanagement. For every school like Ayo Fasanmi that fails, a generation of students is denied the quality education they deserve. For every poorly constructed road, communities are cut off, and economic activities are stifled.

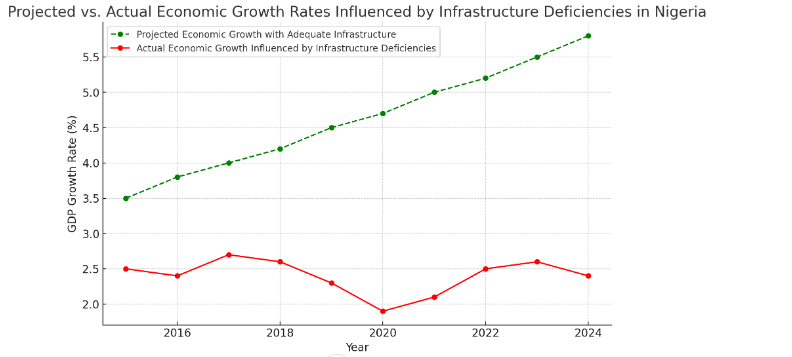

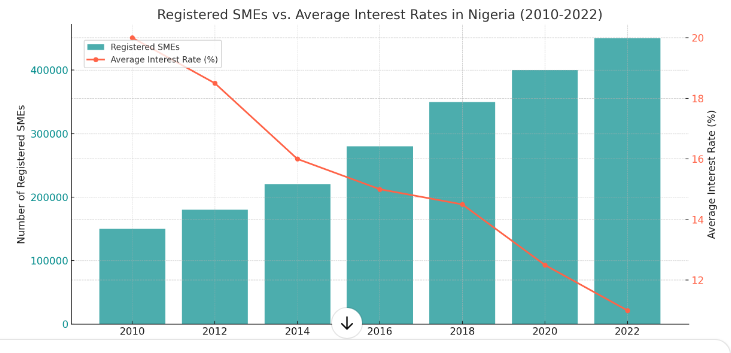

Above is a line chart illustrating The Projected vs. Actual Economic Growth Rates Influenced by Infrastructure Deficiencies in Nigeria. The chart highlights how the actual growth rates, impacted by infrastructure challenges, consistently fall below projected growth. This discrepancy underscores the financial and social costs of project failures, such as diminished economic performance and reduced quality of public services.

Civil servants have a responsibility to uphold project standards, but the reality tells a different story. In many cases, they use bureaucratic bottlenecks to delay projects deliberately, waiting for “facilitation fees” or bribes to move things along. This extortion-driven system fosters an environment where only those willing to play along get anything done. The result? A national economy held hostage by inefficiency, where only a few profit at the expense of the many.

In Nigeria, politicians are often in the public eye, scrutinized for their actions and decisions. But civil servants—especially the elite cadre within ministries and agencies—quietly hold enormous power and wealth. These individuals have spent decades in public office, working in finance, administration, and key operational roles. Many have accumulated more wealth than politicians, thanks to their steady, often hidden control over funds and projects.

In truth, civil servants, from Directors of Finance to Permanent Secretaries, shape the flow of public funds, sometimes siphoning off enormous sums for personal use. The layers of bureaucracy in Nigeria’s civil service allow these individuals to operate with little accountability, and because they are less visible than politicians, they often avoid public scrutiny. But the wealth they accumulate isn’t a byproduct of hard work—it’s a byproduct of the system that allows them to sabotage national projects and profit from inefficiency.

Read Also: The Devastating Impact of Rampant Corruption in Nigerian Society

The consequences of unchecked civil service corruption aren’t just a few cracked walls or abandoned projects. This inefficiency holds Nigeria back from true economic progress, draining public funds and resources that could otherwise drive development. Imagine a Nigeria where every public servant was truly committed to their role, and where every project was completed to high standards. This vision isn’t impossible, but it requires accountability, transparency, and reform.

So, what’s at stake if we allow this system to continue unchanged? More schools like Ayo Fasanmi will be closed. More roads and bridges will crumble before they even see full use. Entire generations of Nigerians will grow up disillusioned, living in a nation where public service is more a punchline than a duty. We cannot ignore the urgency of this issue.

We must recognize the power civil servants wield and demand accountability for every penny spent. Strengthening anti-corruption agencies, establishing independent oversight bodies, and ensuring transparency in project management are crucial steps. But reforms cannot stop at policy changes. We need a shift in mentality—a revival of the ethics that should guide public service.

Religious and community leaders, too, have roles to play. They can encourage civil servants to act with integrity, creating a moral foundation that rejects corruption. Community involvement is equally critical. Hold officials accountable, demand transparency, and refuse to accept the excuse that “this is just how things are.” The civil service must be restored to a position of integrity if Nigeria is ever to move forward.

Our schools, our roads, our healthcare systems—all these are affected by the actions of those who manage public funds. Civil servants must remember that the projects they oversee are not just jobs but responsibilities with real-life consequences. As citizens, we must demand more. The Ayo Fasanmi Model College tragedy is a wake-up call, a glaring reminder of the need for accountability.

If we don’t act now, future generations will inherit the same broken systems, a stagnant economy, and a society where trust in public institutions is non-existent. It’s time to unmask the silent saboteurs of Nigeria’s progress and hold them accountable for their role in the country’s development. Only then can we build a Nigeria that truly serves its people, a nation where every public servant works for the common good?

This dialogue isn’t just about Ayo Fasanmi Model College. It’s about every poorly executed project, every diverted fund, and every Nigerian who suffers as a result. We deserve better, and it’s time we demanded it.

References:

World Bank Group. (2023). Nigeria Public Sector Investment and Infrastructure Report. World Bank.

World Bank Group. (2022). Africa Infrastructure Country Diagnostic (AICD) Report on Nigeria.

International Monetary Fund (IMF). (2021). Nigeria Economic Outlook and Sectoral Investment Needs.

African Development Bank (AfDB). (2020). Nigeria: Infrastructure Financing and Economic Growth Report.

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). (2019). Corruption in Nigeria: Bribery as Experienced by the Population.

BudgIT Nigeria. (2022). Failing Projects: Nigeria’s Economic and Social Costs of Infrastructure Gaps.

Born in Ekiti State, Nigeria, Idowu Faleye is a Policy Analyst and IBM-certified Data Analyst with an academic background in Public Administration. He’s the Lead Analyst at EphraimHill Data Consult and the Publisher of EphraimHill DataBlog, which posts regular topics on issues of public interest. He can be reached via WhatsApp at +2348132100608 or email at ephraimhill01@gmail.com. © 2024 EphraimHill DC. All rights reserved.

![The Trend of Insecurity in Nigeria. [Part 2]](https://ephraimhilldc.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Computer-Monitoring-of-Remote-areas.png)