[By Idowu Faleye: +2348132100608]

Nigeria, with its complex history of governance, is once again facing calls for a return to regionalism. From its inception as a colony, through its early years as an independent state, Nigeria has oscillated between centralised and regional forms of governance. The current federal system, adopted after years of military rule, was intended to unite the country under a single political structure. But today, more than ever, the cracks in this system are evident, and regionalism is being touted as a possible solution to Nigeria’s myriad problems.

However, this road back to regionalism is far from simple. The layers of political influence, entrenched interests, and legislative roadblocks make it a Herculean task for those advocating for this change. At the heart of these roadblocks lies the Fulani oligarchy, a political class whose influence has shaped the nation’s direction since independence. For them, the push for regionalism represents a direct threat to their dominance, making the process an uphill battle. To fully understand the scope of this challenge, we must first dive deep into the historical context, the power dynamics between the North and South, and the strategic political manoeuvring required to make regionalism a reality.

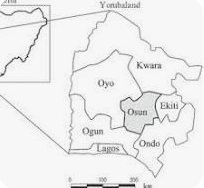

Nigeria’s political history has been shaped by two key forms of governance: federalism and regionalism. In the years immediately following independence, Nigeria operated a regional system where the country was divided into three (later four) regions. These regions had significant autonomy, with control over key areas such as education, healthcare, and internal security.

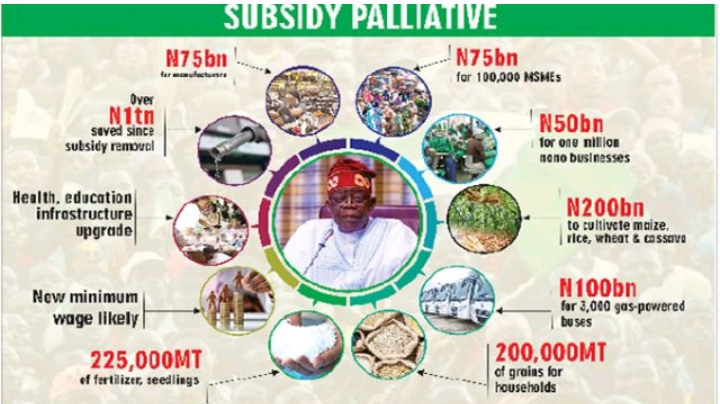

The federal system was introduced to consolidate the regions under a unified government, particularly after the civil war of 1967-1970. This was intended to prevent the secession of regions and promote national unity. However, over time, it became apparent that this federal structure created its own set of problems, particularly in terms of resource allocation, political representation, and ethnic tensions. Today, the call for regionalism is a reflection of these unresolved issues, especially as marginalized groups seek greater control over their affairs.

Read Also: The Undefined System of Government in Nigeria: A Call for True Federalism

The process of returning to regionalism is not as simple as passing a bill through the National Assembly. The Nigerian constitution is one of the most rigid in the world, making amendments both cumbersome and politically charged. For any significant change to take place, it requires not just the support of a majority in the National Assembly but also the backing of at least two-thirds of state houses of assembly. This means that, for regionalism to be realized, a broad political consensus is necessary—something that is notoriously difficult to achieve in a country as diverse as Nigeria.

To put it into perspective, even relatively simple amendments, such as changing election dates or increasing minimum wage, have faced stiff opposition in the past. Regionalism, which would involve a complete overhaul of the current federal structure, is an even more daunting task. The process is likely to be met with fierce resistance, particularly from entrenched interests who benefit from the status quo.

One of the most formidable barriers to regionalism lies in the political structure dominated by the Fulani oligarchy. This class has historically held significant sway over national politics, often shaping policies in ways that protect their interests. The Fulani political elite has used its influence to maintain a strong centralized government, which allows them to control resources and wield power across the country.

Historically, whenever a policy that threatens this centralization is proposed, the oligarchy has set up roadblocks to prevent it from advancing. From opposition to state policing to resource control, the Fulani oligarchy’s influence has been a constant in Nigeria’s political landscape. For regionalism to have any chance of success, its proponents will need to devise strategies to either win over this powerful group or neutralize its opposition.

Read Also: The Trend of Insecurity in Nigeria. [Part 2]

To pass any significant constitutional reform in Nigeria, such as regionalism, political consensus is key. This is particularly true for reforms that challenge the existing power structure. Simply put, regionalism cannot be passed as a regular bill. It requires broad support from both Northern and Southern regions, and more importantly, from key political players in the National Assembly.

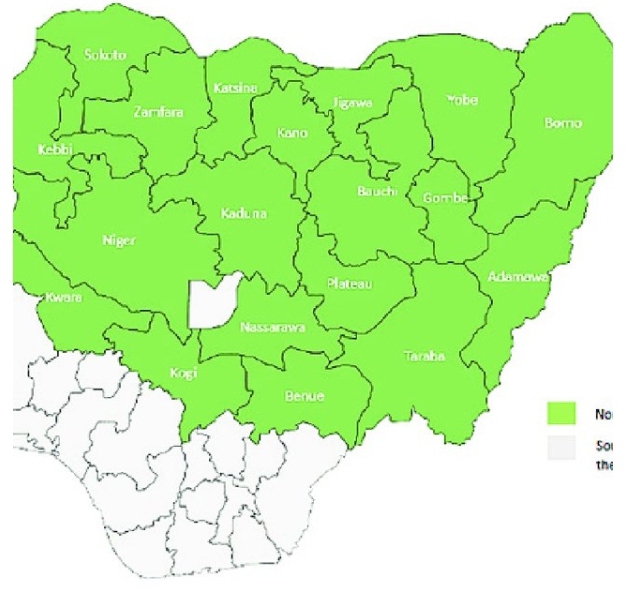

One critical factor in this equation is that Nigeria’s political structure is heavily tilted in Favor of the North. This power imbalance is rooted in the distribution of states and representation in the National Assembly. The North’s 19 states plus the FCT give them a commanding presence in the Senate and the House of Representatives. By contrast, the South’s 17 states represent a political minority, leaving Southern lawmakers at a disadvantage when pushing for reforms like regionalism. For any bill to scale through the National Assembly, it must have the support of a majority of lawmakers or at least be neutral to Northern interests. A bill perceived as anti-North will face stiff resistance, making regionalism a difficult sell without significant lobbying and political manoeuvring.

This imbalance has had a profound impact on policy-making in Nigeria. Historically, policies that are perceived as favouring the North have been pushed through with relative ease, while those seen as anti-North have been blocked. The regionalism bill, which seeks to decentralize power and give more autonomy to the states, is likely to be viewed as a threat to Northern dominance, making it a hard sell in the current political climate.

To overcome the political hurdles of regionalism, proponents must strategically target key states in the North Central Zone for support. This includes states that have long-standing grievances against Northern dominance, such as Benue, Plateau, and the Yoruba parts of Kogi and Kwara. These states and part of states have historically resisted Northern control and could serve as important allies in the push for regionalism.

Read Also: 2023 Population Census: A Necessity for Addressing Nigeria’s Problems

The strategy for gaining support in these states must involve both political, religious, and traditional leaders. Quiet diplomacy and behind-the-scenes negotiations will be crucial in winning over influential figures who can sway their representatives in the National Assembly. Proponents must also emphasize how regionalism benefits not just the South but also Northern minorities, framing it as a solution that promotes national unity and development.

The Fulani oligarchy’s political influence cannot be underestimated. For decades, this group has successfully set up barriers against policies perceived as unfavourable to their interests. The regionalism bill will likely be seen as a direct challenge to their dominance, and they will undoubtedly mobilize their resources to block it.

Read Also: The Injustice of a Northern Presidency in 2027

However, the above-proposed strategies can be employed to counter opposition to return to regional government. Supporters of regionalism can build a broader coalition of support by engaging with key stakeholders and leaders in the Northern states where there is opposition to Fulani dominance. Political, religious, and traditional leaders in these states must be approached carefully and under the cover of quiet diplomacy. These leaders hold the power to influence their representatives in the National Assembly and can be instrumental in securing the necessary votes to pass the bill.

Proponents must also ensure that the benefits of regionalism are clearly communicated to these stakeholders. By showing how regionalism can address their specific grievances and promote local development, supporters can make a compelling case for why the bill deserves their backing.

Read Also: The Northern Political Agenda and the Antics of El-Rufai’s Political Game

The return to regionalism in Nigeria is not just a political issue but a deeply emotional one. It speaks to the desire for self-determination, local autonomy, and the rectification of historical wrongs. However, the road to achieving this goal is fraught with challenges. From the complexity of amending the constitution to the entrenched interests of the Fulani oligarchy, proponents of regionalism face an uphill battle.

To make regionalism a reality, strategic lobbying, political consensus-building, and the careful targeting of key states will be crucial. This is a long-term fight, one that will require patience, persistence, and a clear vision for the future of Nigeria. Ultimately, the success of regionalism depends on the ability of its supporters to build a broad coalition that transcends ethnic and regional divides and to make the case that this is not just a Southern issue but a national one.

Read Also: The Alarming Rise of Fulani Militias in the South and the Inaction of Southern Leaders

The Fulani oligarchy is watching, waiting, and prepared to outvote it. But with the right strategy, regionalism can be the key to unlocking Nigeria’s full potential, creating a more equitable and just political system for all its people.

A return to regional government in Nigeria will not happen without continued dialogue, strategic lobbying, and the building of political alliances. It is up to the people of Nigeria to demand a system that works for them and to push their representatives to make regionalism a reality. The future of Nigeria depends on it.

References

Diamond, L. (1988). Class, Ethnicity, and Democracy in Nigeria: The Failure of the First Republic. Syracuse University Press.

Suberu, R. T. (2001). Federalism and Ethnic Conflict in Nigeria. United States Institute of Peace.

Adejumobi, S. (2015). Governance and Politics in Post-Military Nigeria: Changes and Challenges. Palgrave Macmillan.

Nigeria Bureau of Statistics (NBS). (2022). Nigeria’s Socio-Economic Landscape Report.

Obi, C. I. (2004). “Reconstructing the State in Africa: The Politics of Power and Political Economy of Reform in Nigeria.” Journal of Contemporary African Studies, 22(1), 1-25.

Ukiwo, U. (2003). “Politics, Ethno-religious Conflicts and Democratic Consolidation in Nigeria.” The Journal of Modern African Studies, 41(1), 115-138.

Premium Times. (2023, July 15). “Nigeria’s Power Imbalance: Why the Northern States Have Greater Political Control.”

Vanguard. (2023, August 10). “Constitutional Reform: A Herculean Task for Advocates of Regionalism.”

Centre for Democracy and Development (CDD). (2022). “Nigeria’s Political Structure and the Challenges of Federalism.”

Institute for Governance and Development (IGD). (2023). “The Politics of Regionalism in Nigeria: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives.”

Brookings Institution. (2023). “Reforming Nigeria’s Governance: The Debate Over Federalism and Regionalism.”

Born in Ekiti State, Nigeria, Idowu Faleye is a Policy Analyst and IBM-certified Data Analyst with an academic background in Public Administration. He’s the Lead Analyst at EphraimHill Data Consult and the Publisher of EphraimHill DataBlog, which posts regular topics on issues of public interest. He can be reached via WhatsApp at +2348132100608 or email at ephraimhill01@gmail.com

© 2024 EphraimHill DC. All rights reserved.This article is the intellectual property of EphraimHill DataBlog. For permission requests, please contact EphraimHill DC at ephraimhill01@gmail.com.

![The Trend of Insecurity in Nigeria. [Part 2]](https://ephraimhilldc.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Computer-Monitoring-of-Remote-areas.png)