[By Idowu Faleye: +2348132100608]

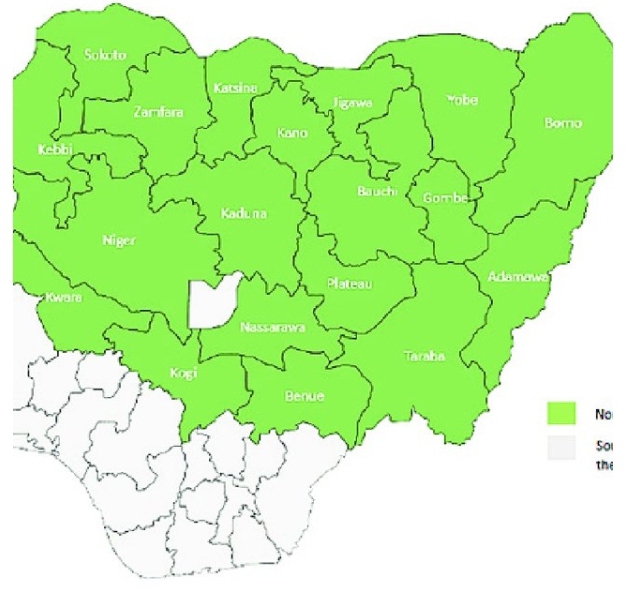

Insecurity has become a problem creeping into every corner of Nigeria. From the bomb-laden roads of Borno to the blood-stained farmlands of Benue, no region remains untouched by the hand of violence. Despite advances in technology, the Nigerian government has failed to deploy the computer-based solutions needed to combat this menace, instead relying on outdated methods in an age where data and intelligence could tip the scales in favour of peace.

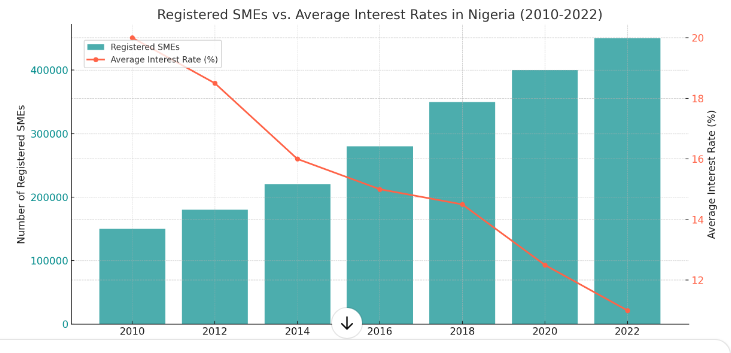

In data analysis, a “trend” refers to the patterns and directions certain phenomena take over time. Identifying these trends is vital for uncovering the causes behind complex social issues, and creating solutions tailored to specific needs. Insecurity in Nigeria has followed a disturbing upward trend in recent years, with major criminal activities like terrorism, banditry, kidnapping, and ethnic violence surging.

Nigeria’s insecurity has taken many forms, with Boko Haram, Fulani herdsmen, and bandits at the forefront. Each group brings a unique threat, but all are bound by their ability to wreak havoc. Yet, despite these clear and escalating patterns, the government continues to underutilize the power of technology. Computer systems that could track crimes, analyze data, predict trends, and create actionable intelligence are left unused. This oversight is dangerous and costly for a country fighting a hydra-headed security problem.

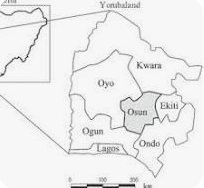

Since 2009, Boko Haram has waged an unrelenting war in Nigeria’s northeast. With over 35,000 deaths attributed to their campaign of terror, they remain one of the most dangerous terrorist groups in the world. The Global Terrorism Index consistently ranks Nigeria among the top three nations most affected by terrorism, largely due to Boko Haram’s activities. In addition to the loss of life, the group has displaced over 2.4 million people, leaving entire towns and villages desolate.

Read Also: The Undefined System of Government in Nigeria: A Call for True Federalism

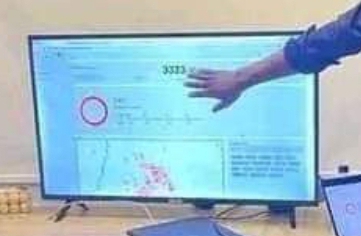

This insurgency thrives in a landscape where surveillance systems, drone technology, and intelligence software are sorely missing. Imagine if Nigeria had deployed sophisticated data systems to track Boko Haram’s recruitment strategies—many of which target (Almajiri) street children from the region—or to monitor the porous borders through which weapons and fighters enter. It’s not just a lack of will but also a lack of technological vision.

Fulani herdsmen, who have turned into a militia over the years, are responsible for some of the deadliest attacks in central Nigeria. Between 2017 and 2021, over 8,000 people were killed in farmer-herder clashes, mostly in Benue, Plateau, and Kaduna states. Beyond the human toll, the violence has devastated agriculture in the Middle Belt, with the National Bureau of Statistics estimating over ₦1.2 trillion in losses between 2017 and 2020.

These conflicts, like Boko Haram’s insurgency, are another area where technology could play a crucial role. Satellite imagery and data analytics could help predict herder movements and allow for preventive measures. Yet again, Nigeria’s failure to leverage these tools has led to continued bloodshed and economic decline.

The rise of banditry in northern Nigeria is one of the most alarming trends in recent years. Armed groups, often composed of disillusioned youth or foreign mercenaries, engage in mass kidnappings, raids, and extortion, primarily in states like Zamfara, Kaduna, and Katsina. Kidnapping for ransom has become a profitable venture, with bandits demanding millions for the release of their victims. In 2022 alone, over 3,000 kidnapping cases were reported, and these are only the documented ones.

Read also: African Poverty is Not an Act of God

The tragic irony is that bandits operate in areas where network connectivity is often poor. Still, if Nigeria embraced technology like drone surveillance and real-time data tracking, this criminal empire could be weakened. For instance, bandits who communicate through mobile phones could be intercepted and their locations tracked.

Kidnapping in Nigeria has evolved into a full-scale industry. While northern kidnappers focus on travellers along highways, southern groups tend to target the wealthy. Ransoms range depends on the victim’s perceived wealth. Between 2018 and 2023, an estimated ₦2 billion was paid in ransoms, enriching criminals while weakening law enforcement.

The southeast, home to the Igbo ethnic group, has seen over 1,200 kidnappings during this same period. The Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB) and its calls for secession have also added another layer to Nigeria’s already complex security puzzle. Led by Nnamdi Kanu, IPOB has led protests, clashed with military forces, and launched targeted attacks on government infrastructure. The group has drawn widespread support from the Igbo diaspora, contributing to both the political tension and economic loss in the southeast. IPOB’s sit-at-home orders alone have cost the southeastern economy billions of naira in lost revenue.

Again, intelligence systems could track IPOB’s movements, identify key players, and perhaps even predict the next protests. But without this crucial technological support, the Nigerian government is left reacting instead of preventing these crises. Meanwhile, in the southwest, a disturbing trend of “self-kidnapping” has emerged, where individuals fake their own abductions to extort family members. These crimes, while seemingly opportunistic, follow clear patterns—patterns that could be analyzed and disrupted using data analysis. However, the lack of political will and investment in technology leaves these regions vulnerable.

Countries around the world have turned to technology to combat insecurity, from drones and facial recognition software to data-driven policing. Yet Nigeria lags, relying instead on manual operations and sheer numbers. This outdated approach is simply not enough to counter the scale and complexity of modern security challenges.

For instance, a robust surveillance network could monitor highways, markets, and rural areas for signs of criminal activity. Drones could be deployed to hard-to-reach areas, offering real-time intelligence to security forces. More importantly, data analysis could help authorities predict crime trends, allowing them to intervene before incidents occur.

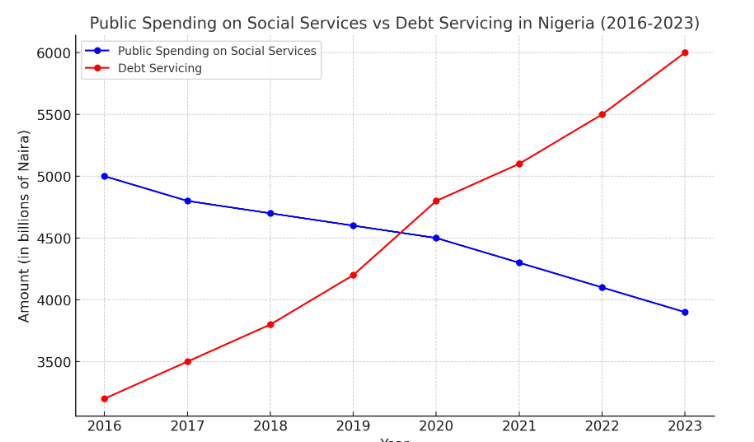

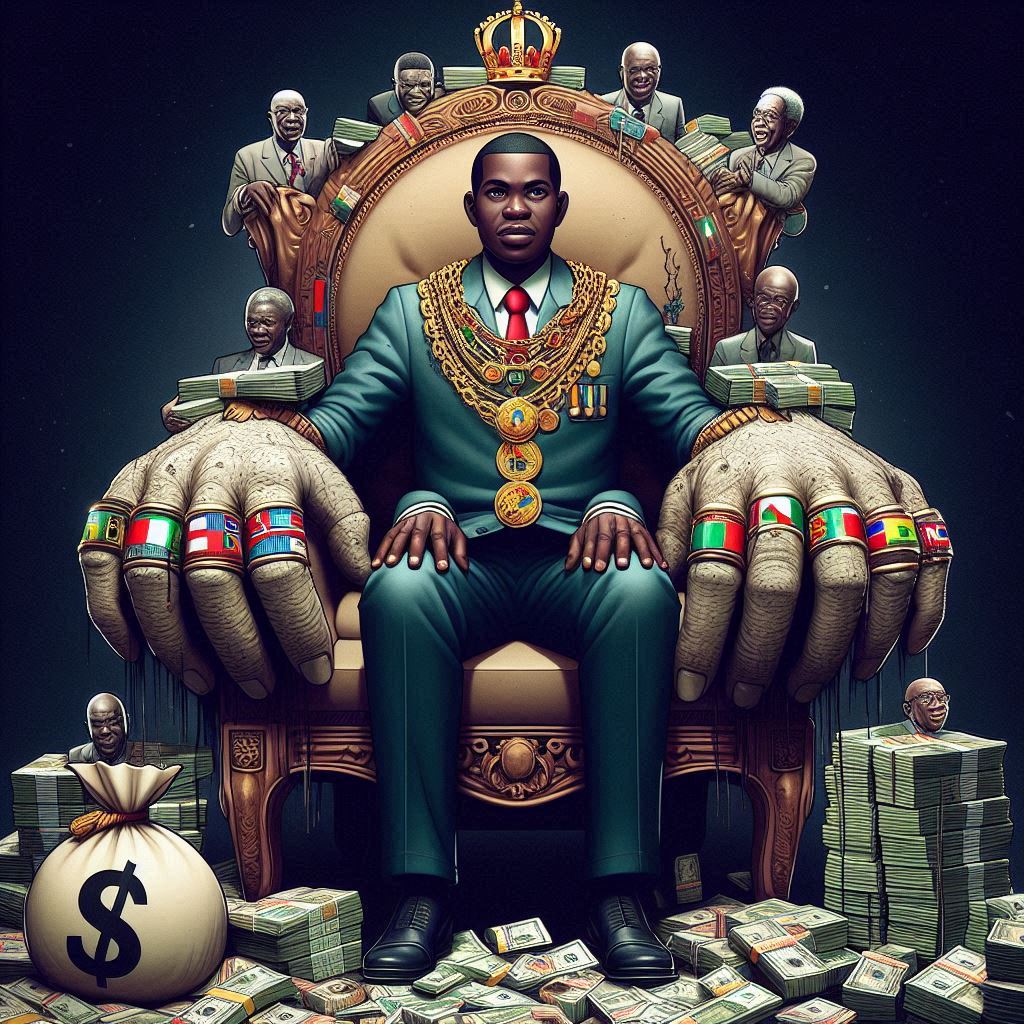

The final and perhaps most tragic element of Nigeria’s insecurity is the lack of political will to combat it. In many cases, officials seem more concerned with securing their positions than securing the nation. Corruption within the ranks of law enforcement and the military only exacerbates the problem, as funds meant for security are often misappropriated.

Without strong leadership and the political determination to implement necessary reforms, insecurity will continue to fester. Worse yet, this lack of action is tearing at the fabric of Nigeria’s national unity. In the southeast, calls for secession grow louder, while in the north, terrorism and banditry persist.

Read Also: The Hidden Margins Between Politics and Governance in Nigeria

The trends in Nigeria’s insecurity are clear—terrorism, banditry, kidnapping, and ethnic violence are on the rise. But just as clear is the solution: technology. With the right tools in place, Nigeria could track, analyze, and predict crime in ways that would drastically reduce the threat to its citizens. Until this happens, the country will remain stuck in a cycle of violence, with thousands of lives lost and billions of naira drained from the economy.

Due to the depth of this crisis, a continuation will follow in the next article, where we will further dissect the gravity of the situation and offer a clear path into how Nigeria can adopt these technologies and use data and intelligence to combat insecurity.

Stay tuned—this discussion is far from over.

References:

Global Terrorism Index 2023

National Bureau of Statistics, Nigeria: Report on the Economic Impact of Farmer-Herder Clashes (2017-2020)

Nigerian Police Force Crime Statistics (2018-2023)

Displacement Tracking Matrix, International Organization for Migration (2023)

Born in Ekiti State, Nigeria, Idowu Faleye is a Policy Analyst and IBM-certified Data Analyst with an academic background in Public Administration. He’s the Lead Analyst at EphraimHill Data Consult and the Publisher of EphraimHill DataBlog, which posts regular topics on issues of public interest. He can be reached via WhatsApp at +2348132100608 or email at ephraimhill01@gmail.com

© 2024 EphraimHill DC. All rights reserved.This article is the intellectual property of EphraimHill DataBlog. For permission requests, please contact EphraimHill DC at ephraimhill01@gmail.com.

![The Trend of Insecurity in Nigeria. [Part 2]](https://ephraimhilldc.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Computer-Monitoring-of-Remote-areas.png)